CSU IS AN IMMUNE-MEDIATED INFLAMMATORY SKIN DISEASE

CSU is characterized by the following:

Spontaneous appearance of wheals and/or angioedema that recur for 6 weeks or more, occurring on most days of the week1–4

Wheals2,5

- Central swelling surrounded by reflex erythema that can appear anywhere on the body

- Accompanied by an itch or burning sensation

- Lesions may resolve within 24 hours while new lesions appear elsewhere

Angioedema2–6

- Sudden, pronounced erythematous or skin-colored swelling of the deep dermis and subcutis, or mucous membranes that can last up to 72 hours

- Often localized. Commonly affects the face, lips, cheeks, tongue, hands, feet, and genitalia

- Sometimes pain, rather than itch

- Present in around half of patients

Chronicity7–9

The average duration of CSU is reported as 1–5 years, but may be longer in more severe cases

Intense itch1,2,4

TPatients rate itch as the most bothersome symptom of CSU7

Significant burden on quality of life:

Sleep disturbance5*,10**

Most people with CSU (92%) experience sleep problems

Appearance5*,10**

People with CSU ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ feel:

Self-conscious and embarrassed (75%)

Less attractive than they used to (68%)

Social interactions5*,10**,11

People with CSU often report that their disease leads to:

Interference with sexual relationships (73%)

Avoidance of other people (51%)

Withdrawal from social activities (63%)

Decreased work productivity and increased absenteeism

Mental health12†,13*‡

The most common mental health disorders among patients with CSU are:

Anxiety disorders (31%)

Mood disorders (29%)

Traumatic and stress-related disorders (17%)

CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria.

*Study pertains to patients with chronic urticaria

**In ASSURE-CSU study with 673 CSU patients

†In a survey of 2,579 dermatology patients

‡A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Magerl M, et al. Allergy. 2016;71(6):780–802;

- Saini SS. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34(1):33–52;

- Radonjic-Hoesli, et al. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):88–101;

- Zuberbier T, et al. Allergy. 2018;73(7):1393–1414;

- O’Donnell BF. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34(1):89–104;

- Sussman G, et al. Allergy. 2018;73(8):1724–1734;

- Maurer M, et al. Allergy. 2011;66(3):317–330;

- Kim YS, et al. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10(1):83-87;

- Gaig P, et al. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14(3):214–220;

- Maurer M, et al. Allergy. 2017;72(5):2005–2016;

- Balp MM, et al. Patient. 2015;8551–8;

- Picardi A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(5):983–991;

- Konstantinou GN. Clin Transl Allergy. 2019,23;42(9);1–12.

CSU LEADS TO LONG-TERM PATIENT BURDEN1-3

Who is affected by CSU?

Global prevalence of

CSU is 0.5–1%4,5

Most patients diagnosed

are 20–40 years old4

CSU is more common in adults than in children6

Twice as many women

are affected as men4,7

CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria.

- Kim YS, et al. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10(1):83–87;

- Gaig P, et al. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14(3):214– 220;

- Maurer M, et al. Allergy. 2017;72(5):2005–2016;

- Maurer M, et al. Allergy. 2011;66(3):317–330;

- Maxim E, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):567–569;

- Anita C, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(4):599–614;

- Cassano N, et al. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151(5):544–552.

CSU IS A MAST CELL-DRIVEN DISEASE, THAT MAY BE INFLUENCED BY A DYSREGULATED TYPE 2 IMMUNE RESPONSE

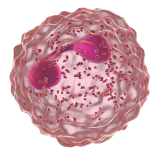

The pathophysiology of CSU is not completely clear, but it is known that mast cells and their degranulation are central1…

Mast cell

...and elements of the type 2 immune response are involved.1 These include:2,3

Eosinophil

Basophil

Th2 cell

ILC2

…and signaling mediators, notably IgE, IgG, and type 2 cytokines4–7

IgE

IgG

IL-4

IL-13

IL-5

IL-31

Histamine

There is heterogeneity in the mechanisms triggering mast cell degranulation

Mast cell degranulation can occur via different mechanisms:*

IgG IgG |

IgE IgE |

Inflammatory mediators Inflammatory mediators |

FcεRI FcεRI |

Self-antigen Self-antigen |

*These mechanisms may also be characterized as autoimmune/type IIb (IgG anti-IgE/IgG anti-FcɛRI) or autoallergic/type I (IgE to self-antigens).

CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; FcεRI, fragment constant (of Ig) receptor; Ig, immunoglobulin; IL, interleukin; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; Th2, T helper 2

CSU LEADS TO LONG-TERM PATIENT BURDEN1-3

Who is affected by CSU?

Global prevalence of

CSU is 0.5–1%4,5

Most patients diagnosed

are 20–40 years old4

CSU is more common in adults than in children6

Twice as many women

are affected as men4,7

-

Multiple aspects of mast cell activity may be influenced by type 2 cytokines

IgG

IgG IgE

IgE Inflammatory mediators

Inflammatory mediators FcεRI

FcεRIMultiple aspects of mast cell activity may be influenced by type 2 cytokines

IgG

IgG IgE

IgE Inflammatory mediators

Inflammatory mediators FcεRI

FcεRI -

IL-4 production contributes to the type 2 inflammatory response

IL-4 promotes the differentiation of Th0 cells into Th2 cells. These Th2 cells then proliferate in response to IL-4 and produce more IL-4, along with other type 2 cytokines, in a positive feedback loop11,10

Type 2 cytokines support mast cell priming4,5

and may contribute to disease features of CSU6–10IL-4 production contributes to the type 2 inflammatory response

IL-4 promotes the differentiation of Th0 cells into Th2 cells. These Th2 cells then proliferate in response to IL-4 and produce more IL-4, along with other type 2 cytokines, in a positive feedback loop11,10

Type 2 cytokines support mast cell priming4,5

and may contribute to disease features of CSU6–10 -

Before degranulation, IL-4 and IL-13 prime mast cells

Type 2 cells, including Th2 cells, basophils, and mast cells, produce IL-4, which drives B-cell class switching.12,13 This leads to IgE and IgG production, which is needed for IgE-dependent and IgE independent degranulation of mast cells8

IL-4 and IL-13 increase IgE receptor (FcεRI) expression, priming mast cells for degranulation15,16

Before degranulation, IL-4 and IL-13 prime mast cells

Type 2 cells, including Th2 cells, basophils, and mast cells, produce IL-4, which drives B-cell class switching.12,13 This leads to IgE and IgG production, which is needed for IgE-dependent and IgE independent degranulation of mast cells8

IL-4 and IL-13 increase IgE receptor (FcεRI) expression, priming mast cells for degranulation15,16

-

After the degranulation of mast cells, IL-4 and IL-13 have broad effects on itch and edema

Inflammatory mediators promote immune cell infiltration

Histamine and other inflammatory mediators cause vasodilation and increased vascular permeability, thereby promoting plasma extravasation23,24

Increased IL-4 signaling can lead to increased skin homing of type 2 inflammatory cells, through VCAM-1 upregulation17

These may lead to the development of edema and pruritus and contribute to disease chronicity22Basophils and eosinophils also contribute to CSU

IL-4 contributes to survival of, and FcεR1 expression by, basophils;28 these cells may have a similar role to mast cells in CSU9

Eosinophils, regulated mainly by IL-5,26 may stimulate mast cell histamine release thereby contributing to edema and itch18 IL-4 and IL-13 are implicated in activating itch sensory pathways

- IL-4 leads to the differentiation and proliferation of Th2 cells, the main source of pruritogen IL-3110,21

- IL-4 and IL-13 sensitizes neurons to the effects of pruritogens IL-31 and histamine21

- IL-4 and IL-13 upregulate the receptor for pruritogen IL-31, increasing its expression in the dermis20

Together, edema and itch lead to reduced patient QoL22

After the degranulation of mast cells, IL-4 and IL-13 have broad effects on itch and edema

Inflammatory mediators promote immune cell infiltration

Histamine and other inflammatory mediators cause vasodilation and increased vascular permeability, thereby promoting plasma extravasation23,24

Increased IL-4 signaling can lead to increased skin homing of type 2 inflammatory cells, through VCAM-1 upregulation17

These may lead to the development of edema and pruritus and contribute to disease chronicity22Basophils and eosinophils also contribute to CSU

IL-4 contributes to survival of, and FcεR1 expression by, basophils;28 these cells may have a similar role to mast cells in CSU9

Eosinophils, regulated mainly by IL-5,26 may stimulate mast cell histamine release thereby contributing to edema and itch18 IL-4 and IL-13 are implicated in activating itch sensory pathways

- IL-4 leads to the differentiation and proliferation of Th2 cells, the main source of pruritogen IL-3110,21

- IL-4 and IL-13 sensitizes neurons to the effects of pruritogens IL-31 and histamine21

- IL-4 and IL-13 upregulate the receptor for pruritogen IL-31, increasing its expression in the dermis20

Together, edema and itch lead to reduced patient QoL22

*These mechanisms may also be characterized as autoimmune/type IIb (IgG anti-IgE/IgG anti-FcɛRI) or autoallergic/type I (IgE to self-antigens).

CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; FcεRI, fragment constant (of Ig) receptor; Ig, immunoglobulin; IL, interleukin; Th2, T helper 2

- Kocatürk E, et al. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:1; Erratum in: Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;3(7):11;

- Ying S, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(4):694–700;

- Wang SH and Zuo YG. Front Immunol. 2021;12:698522;

- Hide M,et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(22):1599–604;

- Kikuchi Y and Kaplan AP. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(1):114–8;

- Ferrer M, et al. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;129(3):254–60;

- Caproni M, et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;36(1):57–9;

- Maurer M, et al. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020;181(5):321– 333;

- Bracken SJ, et al. Front Immunol. 2019;10:627;

- Keegan AD et al. Fac Rev. 2021;10:71;

- Stott B, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Aug;132(2):446–54.e5;

- Brown MA, et al. Cell. 1987; 50(5):809–18;

- Kondo Y, et al. Int Immunol. 2008 ;20(6):791–800;

- Bergstedt-Lindqvist S, et al. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18(7):1073–7;

- Kaur D, et al. Allergy. 2006;61(9):1047–53;

- Toru H, et al. Int Immunol. 1996;8(9):1367–73;

- Cheng LE, et al. J Exp Med. 2015; 212(4):513–24;

- Altrichter S, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(6):1510–6l;

- Bilsborough J, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):418–25;

- Oetjen L, et al. Cell. 2017;171(1):217–228;

- Edukulla R, et al. J Biol Chem. 2015;29(21)0:13510–13520;

- Maurer M, et al. Allergy. 2017;72(5):2005–16;

- Ashina K, et al. PLoS One. 2015; 10(7): e0132367;

- Ohtsu H, et al. Eur J. Immunol. 2002.32:1698–1708;

- Reinhart and Kaufmann. Cell Death Dis 2018.9(7):713;

- Spencer LA and Weller PF. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88(3): 250–6.

CSU TREATMENT SHOULD CONTROL DISEASE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The aim of CSU treatment is to improve patient quality of life through1,2:

Controlling signs and symptoms of CSU

Therapies with a favorable safety and tolerability profile

EAACI/EDF treatment guidelines recommend a four-step approach to treatment1,2

Type 2 mediators beyond IgE may be therapeutic targets for CSU

Despite the use of antihistamines and anti-IgE treatments, some patients are not adequately controlled.3-5

More advanced and specific targeted therapies are needed for safe and effective treatment of these patients

Type 2 inflammation has been suggested to play a role in the disease features and underlying mechanisms of CSU6–8

*As an alternative to anti-IgE therapy

CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; EAACI, European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; EDF, European Dermatology Forum; H1AH; histamine 1 receptor antihistamine; Ig, immunoglobulin.

- Zuberbier T, et al. Allergy. 2021;77(3):734–766;

- Bernstein J, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1270–1277;

- Guillén-Aguinaga S, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(6):1153–1165;

- Min TK and Saini SS. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2019;11(4):470–481;

- Kolkhir P, et al. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(1):2–12;

- Caproni M, et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;36(1):57–59;

- Cevikbas F, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):448–460;

- Feld M, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(2):500–508.

MAT-AE-2300740/V1/January 2024