ESC/EAS Guidelines

Bringing dyslipidaemia management guidelines into practice for your very high-CV- risk patients

Patients are classified as very high CV risk after their first ACS event.1 Aligned with the ESC/EAS guidelines, consider a more aggressive treatment to reach LDL-C goals.1

The 2019 updates to these guidelines “provide important new advice on patient management, which should enable clinicians to efficiently and safely reduce CV risk through lipid modification”.1

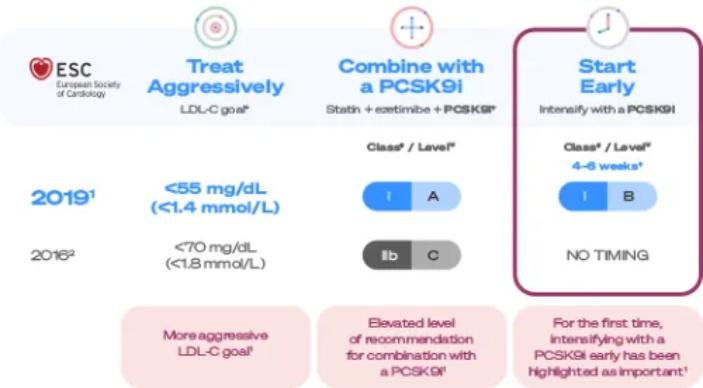

The ESC/EAS 2019 guidelines include treatment recommendations for very high-CV-risk patients1

ESC/EAS guidelines recommend aggressive, combined, and early treatment to lower the future risk of cardiovascular events in your very high-CV-risk patients.1

For the first time, the early treatment of post-ACS patients using a PCSK9i to reduce LDL-C has been highlighted as important in the ESC/EAS 2019 guidelines.1

Data from ACS EuroPath, a Pulse initiative, has highlighted the opportunity to get very high-CV-risk patients to LDL-C goal in clinical practice3§

ACS EuroPath is a pioneering programme on ACS patient pathway optimisation, aiming to improve patient outcomes since 2018.4

- Involving 555 cardiologists and data collected from 2,775 participating patients around Europe3

- Assessing current post-ACS lipid management clinical practices3

.png/jcr:content/ACS_story_RTE5_Europath_v4.2-REV3_03%20(6).png)

Data collected from patient record forms during acute phase and follow-up3

1 year of data collection

including lipid profile, medications, and follow-up visit planning3

Evaluating ACS lipid management compliance to ESC/EAS guidelines3

Compared to ESC/EAS guidelines recommendations, EuroPath data showed the real-world opportunity to treat aggressively with combination therapy early:1,3§

| Treat aggressively | Combine | Start Early | |

| ESC/EAS 2019 Guidelines1 | LDL-C <55 mg/dL (<1.4 mmol/L) AND a ≥50% reduction from baseline |

| Follow up every 4–6 weeks when not at target |

| Reality (ACS EuroPath§) | 87% of LDL-tested patients were not at goal at 2nd follow up5 (n=546/626)5 (68% at 2016 LDL-C goal of <70 mg/dL [n=423/626])2,5 | 75% didn’t receive additional treatment when not at LDL-C goal after 1st follow up3 (n=578/774)5 | 64% are not followed up in <6 weeks3 |

A post-hoc analysis of ODYSSEY OUTCOMES examined how many recent ACS patients achieved the ECS/EAS 2019 LDL-C goal by combining maximally tolerated statins with the use of ezetimibe¶ or alirocumab.6

In ODYSSEY OUTCOMES, early treatment with alirocumab demonstrated a significant 15% RRR in MACE (primary endpoint) in the overall population (HR 0.85 [95% CI 0.78, 0.93], P=0.0003), 2.0% ARR, and is the only PCSK9i associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality in a CV outcomes trial with only nominal statistical significance by hierarchical testing (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73, 0.98).7,8

The safety profile in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES was consistent with the overall safety profile described in the phase 3 controlled trials.8 The only adverse reaction in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES occurring with higher incidence compared to placebo was injection site reaction (P<0.001).7

Proportion of previously uncontrolled patients on maximally tolerated statins ezetimibe or alirocumab achieving updated LDL-C goals6||

.png/jcr:content/Asset%201@2x%20(13).png)

95% of patients achieved the latest LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL with alirocumab in addition to maximally tolerated statins6||

Adapted from Landmesser U et al. 2020.6

Mean time from index ACS to initiation with alirocumab was 2.6 months7

Median baseline LDL-C was 89 mg/dL (interquartile range 73–104)6

ACS= acute coronary syndrome ; ESC European Atheroscleros is Society ; ESC=European Society of Cardiology; LDL-C= low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9i= proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor.

*Jernberg et al.(2015) conducted an observational,retrospective cohort study that analysed data from mandatory Swedish national registries: the National Inpatient Register(inpatient admission and discharge dates, and main and secondary diagnoses according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification(ICD-10-CM codes); the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (all drugs dispensed in Sweden; from 1st July 2005);and the Cause of Death Register ( complete nationwide coverage of date and cause(s)ofdeath).1 A validation of the National Inpatient Register, where MI diagnoses recorded inpatient journals were compared with National Inpatient Register data, revealed that 95% of all MI diagnoses in the National Inpatient Register are valid.1 All drugs were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.1 Individual patient-level data from these registers were linked via the unique personal identification number, which was then replaced by a study identification number prior to further datap rocessing.1 The data included 97, 254 patients admited to hospital with a primary MI between 1st July 2006 and 30th June 2011(primary MI) and alive 1 week after discharge.1 20,567 patients experienced an event with in the primary composite endpoint of risk for non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke or CV death with in the first 365 days post index MI.1 The cumulative rate of the primary composite endpoint (MI,stroke or cardiovascular death) was 13.3% and 18.3% during the first 6 and 12 months, respectively, in the MI population.1 Therefore, of the recurent CV events that occured in the first year post MI,those that happened in the first 6 months has been calclated as 13.3 / 18.3 x 100 = 72.6%.

Primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixeddyslipidaemia5

PRALUENT is indicated in adults with primary hypercholesterolaemia(heterozygous familial and non-familial)or mixed dyslipidaemia,as an adjunct to diet:

- in combination with a statin or statin with other lipid lowering therapies in patients unable to reach LDL-C goals with the maximum tolerated dose of a statin or,

- alone or in combination with other lipid-lowering therapies in patients who are statin-intolerant, or for whom a statin is contraindicated.

Established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease5

PRALUENT is indicated in adults with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease to reduce cardiovascular risk by lowering LDL-C levels, as an adjunct to corection of other risk factors:

- in combination with the maximum tolerated dose of a statin with or without other lipid-lowering therapies or,

- alone or in combination with other lipid-lowering therapies inpatients who are statin-intolerant, or for whom a statin is contraindicated.

ODYSSEY OUT COMES was a randomised double-blind, placebo-controledphase 3 study.5,6~19,000 patients were randomised all patients had experienced a prior CV event defined as myocardial infarction or unstable angina with2.6 months median time post index event to randomisation.5,6§ ~90% were on high-intensity statins ( atorvastatin 40 or 80 mg/day or rosuvastatin 20 or 40 mg/day).6| The safety profile in ODYSSEY OUT COMES was consistent with the overall safety profile described in the phase 3 controled trials.5 The only adverse reaction in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES occuring with higher indence compared to placebo was injection site reaction (3.8% in the alirocumab group vs. 2.1% in the placebo group, P<0.0001).6

*Data from the ACS Patient Pathway Project. By means of a 45-minute online questionnaire,data on 2,775 ACS patients(either acute case or follow-up patients) were collected from 555 cardiologists across 7 European countries (France,Germany,Italy,Spain,United Kingdom,Switzerland and the Netherlands) including data on lipid profile, medications,follow-up visit planning,screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia. The aim of this survey was to evaluate the compliance to curent ESC/EAS guidelines during management of ACS and the effectiveness of secondary prevention in post-ACS patients.2

†EAS/ESC 2019 guidelines recommend lipid levels should be re-evaluated 4–6 weeks after ACS to determine whether a reduction of > 50% from baseline and goal levels of LDL-C < 55mg/dL have been achieved.If the LDL-C goal is not achieved after 4–6 weeks with the maximally tolerated statin dose combination withezetimibeis recommended.If the LDL-C goal is not achieved after 4–6 weeks with the maximally tolerated statin dose and ezetimibe,the addition of a PCSK9i is recommended.3

‡A post-hoc assessment using data from the ODYSSEY OUT COMES trial. DYSSEY OUT COMES enroled 18,924 patients with an ACS event with in 12 months of enrolment and LDL-C>70 mg/dL,non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol>100 mg/dL or apolipoprotein B>100 mg/dL despite intensive or maximally tolerated statin treatment. Patients were randomised to receive alirocumab or placebo and the proportion of patients achieving updated LDL-C goals of < 55 mg/dL at least one post-baseline measurement are presented.6OUTCOMES was consistent with the overall safety profile described in the Phase 3 controled trials.5 The only adverse reaction in ODYSSEY OUT COMES occuring with higher incidence compared to placebo was injection site reactions(3.8% in the alirocumab group vs 2.1% in the placebogroup; P< 0.001).6

¥ESC/EAS guideline definition of very high risk = people with any of the following: documented ASCVD, either clinical or unequivocal on imaging; DM with target organ damage( microalbuminuria, retinopathy, or neuropathy),or at least 3 major risk factors, or early onset of Type 1DM of long duration(>20years);severe chronic kidney disease(estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2); a calculated systematic coronary risk evaluation>10% for 10-year risk of fatal CV disease; familial hypercholesterolaemia with ASCVD or with another major risk factor.3

§Patients were randomised for 1 to 12 months after an acute coronary syndrome and had an LDL-C≥70mg/dL or non-HDL-C≥100 mg/dL,or an ApoB of≥80 mg/dL.6Background theraphy: 96% aspirin; 88% P2Y12 inhibitor; 85% beta blocker; 78% AC/ARBs.7

ACE = angiotensin-coverting enzyme; ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ARBs = angiotensin II receptor blockers; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CV = cardiovascular; DM = diabetes mellitus; EAS = European Atherosclerosis Society; ESC = European Society of Cardiology; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9i = proprotein covertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor;

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111–188.

- Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G,et al. and the ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(39):2999–3058.

- Landmesser U, Pirillo A, Farnier M, et al. Lipid-lowering therapy and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal achievement in patients with acute coronary syndomes: The ACS patient pathway project. Atheroscler Suppl. 2020;42:e49–e58.

- Sionis A, Catapano AL, De Ferrari GM, et al. Improving lipid management in patients with acute coronary syndrome: The ACS Lipid EuroPath tool. Atheroscler Suppl. 2020;42:e65–e71.

- Landmesser U, Pirillo A, Farnier M, et al. Lipid-lowering therapy and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal achievement in patients with acute coronary syndomes: The ACS patient pathway project. Atheroscler Suppl. Suppl. 2020;42:e49–e58.

- Landmesser U, McGinniss J, Stegg G, et al. Achievement of new European dyslipidaemia-guideline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol treatment goals after acute coronary syndrome: insights from ODYSSEY OUTCOMES. Presented at ACC – Chicago, USA. March 28–30 2020.

- Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2097–2107.

- PRALUENT (alirocumab) Summary of Product Characteristics. Gulf SmPC, revision date: November 2020 & KSA SmPC, revision date: June 2021

- Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2097–2107. Supplementary Appendix.

-REV-(9).png/jcr:content/banner%20(2400x600)%20REV%20(9).png)