Treat Early

Act now for your post-ACS patients to reduce their CV risk

After their first ACS event, patients are classified as very high CV risk by ESC/EAS 2019 guidelines, regardless of comorbidities.1

To address this elevated risk, the European guidelines now highlight early treatment with a PCSK9i as important for the management of dyslipidaemia.1

The approach of early treatment intensification with combined LLT is supported by strong clinical evidence, which demonstrates the benefit of early and prolonged LDL-C reduction for your patients and its impact on future CV outcomes.1,2

Patients are at immediate and elevated risk of a repeat CV event following their first ACS event2

.png/jcr:content/Asset%201@2x%20(11).png)

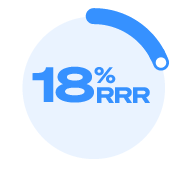

of recurent CV events that occur in the first year post MI happen in the first 6 months1

(cumulative rate of MI, stroke and CV death of 13.3% and 18.3% at 6 and 12months,respectively)1*

These very high-CV-risk patients require rapid LDL-C reduction to reduce their future CV risk.1,2

.png/jcr:content/Asset%201@2x%20(12).png)

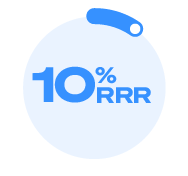

The earlier LDL-C is reduced, the greater the reduction in CHD risk3†

In meta-analyses of prospective epidemiologic studies and clinical data, the earlier LDL-C was reduced the greater the reduction in CHD risk.3†

In ODYSSEY OUTCOMES, early treatment with alirocumab demonstrated a significant 15% RRR in MACE (primary endpoint) in the overall population (HR 0.85 [95% CI 0.78, 0.93], P=0.0003), 2.0% ARR, and is the only PCSK9i associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality in a CV outcomes trial with only nominal significance by hierarchical testing (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73, 0.98).4,5

The safety profile in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES was consistent with the overall safety profile described in the phase 3 controlled trials.5 The only adverse reaction in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES occurring with higher incidence compared to placebo was injection site reaction (P<0.001).5

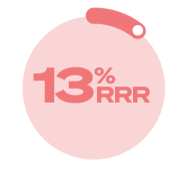

ODYSSEY OUTCOMES post-hoc analysis: relative risk reduction in MACE and all-cause mortality for patients with a first or recurrent ACS with arlirocumab vs placebo6‡¥

- Patients with first ACS > n=15,921

- Patients with a recurrent ACS n=3,633

Median time to randomisation was 2.6 months6

MACE

alirocumab

vs placebo

Added to maximally

tolerated statins

.png)

7.4% vs 8.9%, respectively; HR 0.82

(95% Cl 0.73, 0.92)

.png)

18.6% vs 20.5%, respectively; HR

0.90 (95% CI 0.78, 1.05)

Pinteraction= 0.34

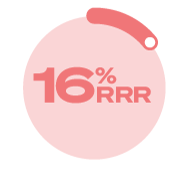

All-Cause

Mortality

alirocumab vs placebo

Added to maximally

tolerated statins

.png)

3.0% vs 3.4%, respectively; HR 0.87

(95% CI 0.72, 1.05)

.png)

6.0% vs 7.4%, respectively; HR 0.84

(95% CI 0.64, 1.08)

Pinteraction= 0.81

This is a post-hoc analysis.¥

Following a first or recurrent ACS, alirocumab significantly reduced MACE and was associated with a reduction in all cause mortality.

This substantial clinical evidence demonstrates the importance of early treatment to reduce the CV risk of your very high-CV-risk patients.

Established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease4

PRALUENT is indicated in adults with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease to reduce cardiovascular risk by lowering LDL-C levels, as an adjunct to correction of other risk factors:

- in combination with the maximum tolerated dose of a statin with or without other lipid-lowering therapies or,

- alone or in combination with other lipid-lowering therapies in patients who are statin-intolerant, or for whom a statin is contraindicated. ODYSSEY OUTCOMES was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study.4,5 ~19,000 patients were randomised; all patients had experienced a prior CV event defined as myocardial infarction or unstable angina with 2.6 months median time post index event to randomisation.4,5 § ~90% were on high-intensity statins (atorvastatin 40 or 80 mg/day or rosuvastatin 20 or 40 mg/day).II The safety profile in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES was consistent with the overall safety profile described in the phase 3 controlled trials.5 The only adverse reaction in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES occurring with higher incidence compared to placebo was injection site reaction (P<0.001).5 Consult the full prescribing information for further details:

*Jernberg et al.(2015) conducted an observational,retrospective cohort study that analysed data from mandatory Swedish national registries: the National Inpatient Register(inpatient admission and discharge dates, and main and secondary diagnoses according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification(ICD-10-CM codes); the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (all drugs dispensed in Sweden; from 1st July 2005);and the Cause of Death Register ( complete nationwide coverage of date and cause(s)ofdeath).1 A validation of the National Inpatient Register, where MI diagnoses recorded inpatient journals were compared with National Inpatient Register data, revealed that 95% of all MI diagnoses in the National Inpatient Register are valid.1 All drugs were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.1 Individual patient-level data from these registers were linked via the unique personal identification number, which was then replaced by a study identification number prior to further datap rocessing.1 The data included 97, 254 patients admited to hospital with a primary MI between 1st July 2006 and 30th June 2011(primary MI) and alive 1 week after discharge.1 20,567 patients experienced an event with in the primary composite endpoint of risk for non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke or CV death with in the first 365 days post index MI.1 The cumulative rate of the primary composite endpoint (MI,stroke or cardiovascular death) was 13.3% and 18.3% during the first 6 and 12 months, respectively, in the MI population.1 Therefore, of the recurent CV events that occured in the first year post MI,those that happened in the first 6 months has been calclated as 13.3 / 18.3 x 100 = 72.6%.

†Data from a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel assessing evidence from genetic, epidemiological and clinical studies. Log-linear association per unit change in LDL-C and the risk of CV disease as reported in meta- analyses of Mendelian randomisation studies (N=”194,427), prospective epidemiologic cohort studies (N=403,50”1), and randomised trials (N=”196,552). The proportional risk reduction (y-axis) is calculated as1-relative risk (as estimated by the odds ratio in Mendelian randomisation studies, or the hazard ratio in the prospective epidemiologic studies and randomised trials) on the log scale, then exponentiated and converted to a percentage.3

‡ODYSSEY OUTCOMES was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. ~19,000 patients were randomised; all patients had experienced a prior CV event defined as myocardial infarction or unstable angina with 2.6 months median time post index event to randomisation. Patients were randomised for 1 to 12 months after an acute coronary syndrome and had an LDL-C acute coronary syndrome and had an LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C ≥100mg/dL, or an ApoB of ≥80 mg/dL. ~90% were on high-intensity statins (atorvastatin 40 or 80 mg/day or rosuvastatin 20 or 40 mg/day). Background therapy: 96% aspirin; 88% P2Y12 inhibitor; 85% beta blocker; 78% ACE/ARBs.7 The safety profile in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES was consistent with the overall safety profile described in the phase 3 controlled trials.4 The only adverse reaction in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES occurring with higher incidence compared to placebo was injection site reaction (P<0.001).5

¥Chiang et al (2021) conducted this prespecified analysis of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial to determine whether a previous history of MI influenced the risk of MACE after ACS and the reduction of that risk with alirocumab treatment.6 §Patients were randomised for 1 to 12 months after an acute coronary syndrome and had an LDL-C acute coronary syndrome and had an LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C ≥100mg/dL, or an ApoB of ≥80 mg/dL.5

IIBackground therapy: 96% aspirin; 88% P2Y12 inhibitor; 85% beta blocker; 78% ACE/ARBs.7

- Jernberg T , Hasvold P, Henriksson M,et al.Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real-world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective. EurHeartJ.2015;36(19):1163–1170.

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al.2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk.Eur Heart J.2020;41(1):111–188.

- Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1.Evidencef rom genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. Aconsensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. EurHeartJ.2017;38(32):2459–2472.

ACS= acute coronary syndrome ; ESC European Atheroscleros is Society ; ESC=European Society of Cardiology; LDL-C= low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9i= proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor.

-REV-(9).png/jcr:content/banner%20(2400x600)%20REV%20(9).png)