Clinical Burden of COPD

| COPD is associated with persistent respiratory symptoms, exacerbations, and inflammation, which contribute to declines in lung function, reduced QOL, and high mortality. |  |

Symptom burden

| Physical |

Persistent symptoms of COPD contribute to patients’ physical debilitation1.

In 2017, COPD was the sixth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide and accounted for the majority of DALYs associated with chronic respiratory disease2,3

I am continually tired. The simplest tasks take ages to complete and leave me exhausted, breathless, and depressed.

Not being able to breathe and unable to do physical activity. The worst part: Your mind tells you that you can do it.

Not being able to breathe and unable to do physical activity. The worst part: Your mind tells you that you can do it.

| Mental |

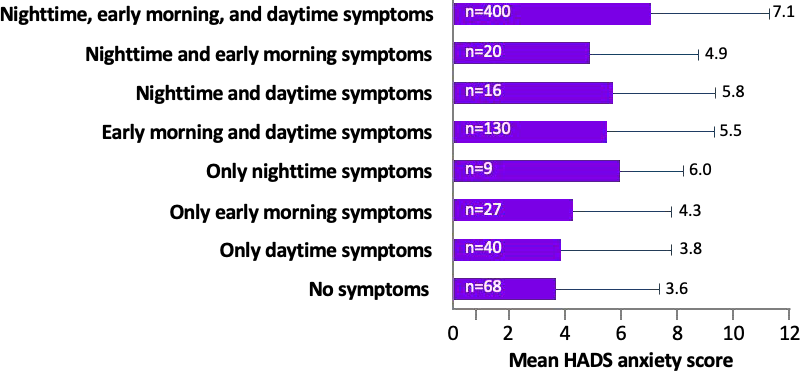

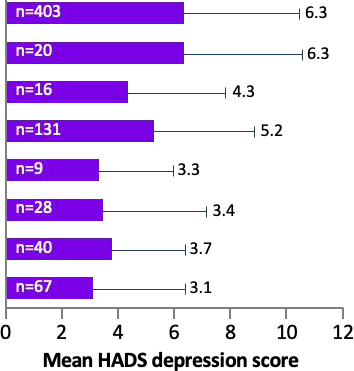

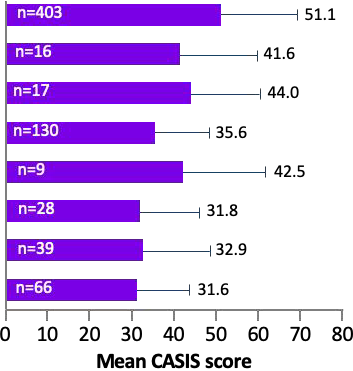

ASSESS was an observational study which enrolled patients with stable COPD in clinical practice and aimed to investigate the relationship between 24-hour symptoms and other patient-reported outcomes4.

Persistent symptoms of COPD were associated with high levels of anxiety and depression, and poor sleep quality, irrespective of whether symptoms occurred in the early morning, daytime, or night time4.

Patients who experienced symptoms throughout the whole 24-hour day experienced the worst levels of impairment4.

Mean anxiety, depression, and sleep quality scores according to the pattern of COPD symptoms throughout the 24 hour day (n=727)4

Anxiety | Depression | Sleep Disturbance |

*0-7 = normal; 8-10 = mild; 11-15 = moderate; 16-21 = severe. Higher scores mean worse sleep quality.,

CASIS, COPD and Asthma Sleep Impact Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Quality of Life

Persistent debilitating symptoms of COPD have a substantial impact on patients' QoL.

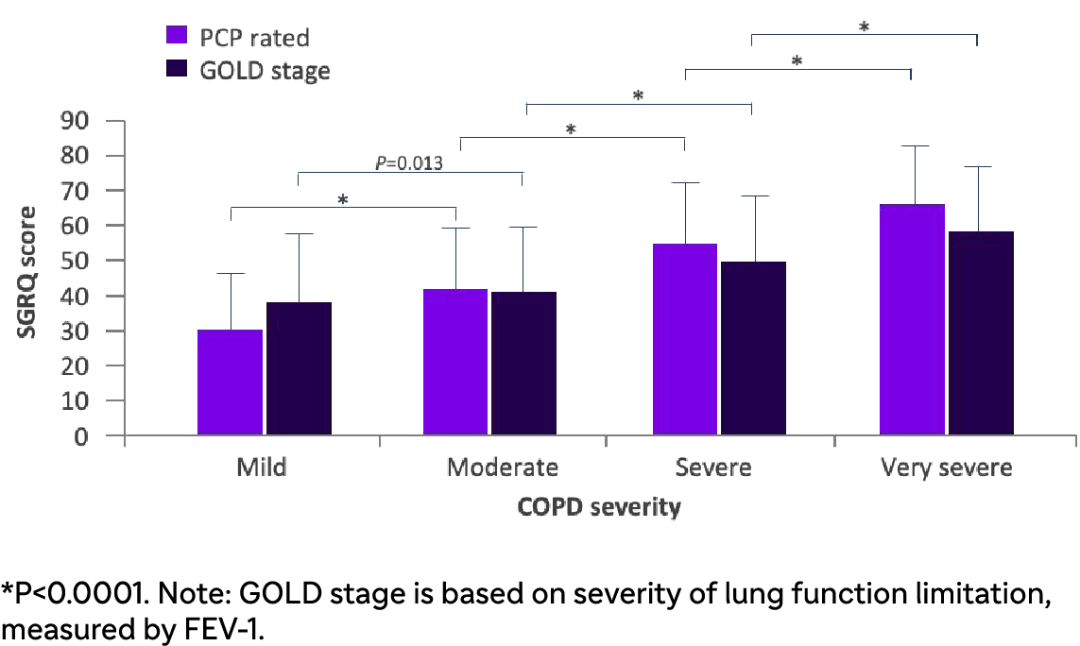

A cross-sectional European observational study illustrated QoL impairment was related to COPD severity:

As disease severity increased, QoL impairment increased, as measured using SGRQ scoress5.

Factors associated with worsening QoL include5:

-

COPD symptoms of breathlessness

-

Cough and excess sputum

-

Exacerbations

-

Lung function decline

-

Hospitalizations

Impairment in QoL related to COPD severity:Data from a cross-sectional European studys5

| In many patients, guilt or shame from their perception of COPD as a "self-inflicted" disease can effect their QoL and interaction with HCPs1. The MIRROR study was conducted in Europe and analysed how perceptions of disease severity and impact on QOL may differ between patients and HCPs. This study found that6:

|

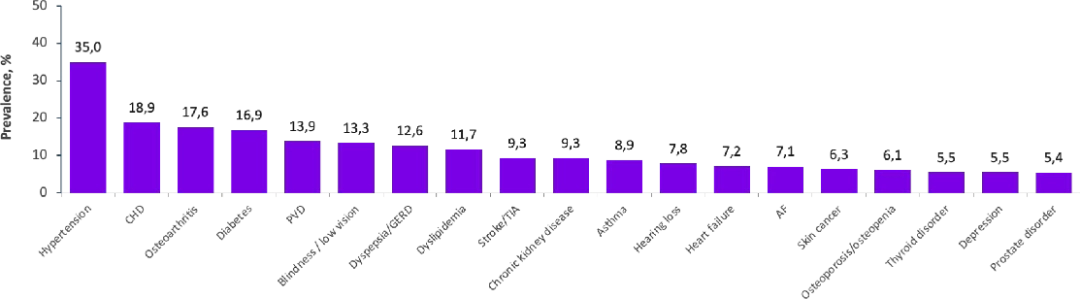

Clinical burden of co-existing conditions in COPD

The inflammatory processes associated with COPD may affect the functioning of extrapulmonary systems, and as a result, COPD patients present with co-existing diseases across a range of organ systems16. This can greatly increase the burden of COPD.

In a retrospective analysis of 14,603 Dutch patients with COPD, 88% had ≥1 co-existing disease16

*The consideration of asthma as a separate co-existing disease from COPD is controversial.

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; AF, atrial fibrilation; CHD, coronary heart disease; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

COPD with co-existing conditions is associated with negative health impact, worse treatment management:

Health Impact

- Patients with COPD and co-existing diseases, such as heart failure, osteoporosis/osteopenia, and asthma have an increased risk of frequent exacerbations16

- COPD and co-existing Asthma also result in increased hospital admissions, whereas COPD and cardiovascular disease has a higher rate of hospitalization and death17,18

Worse treatment management

- 30% of patients with COPD and Asthma have ≥2 records of OCS dispensing over their lifetime vs. 12% of patients with COPD alone19

- Short- and long-term OCS use has been linked to multiple adverse-events20

Exacerbations

Patients with COPD can experience "flare-ups"" which can be defined as general worsening of symptoms as well as more serious exacerbations.

An exacerbation of COPD is defined as an event characterized by increased dyspnea and/or cough and sputum that worsens in <14 days which may be accompanied by tachypnea and/or tachycardia and is often associated with increased local and systemic inflammation caused by infection, pollution, or other insult to the airways21,31.

Exacerbations can be mild, moderate and severe. Severe exacerbations usually require hospitalisation22.

Exacerbations of COPD significantly impact on the health status of a patient, increase the rate of lung function decline, and worsen the prognosis of patients.

Quality of life

In a study of 70 COPD patients, SGRQ total and component scores — a tool used to measure quality of life-were significantly higher in the frequent exacerbator group compared with those who less frequently experienced exacerbations23.

Relationship between SGRQ score and exacerbation frequency23

| Exacerbation frequency | n | SGRQ total score | SGRQ component: Symptoms | SGRQ component: Activities | SGRQ component: Impact |

| 0-2 | 32 | 48.9 ± 15.6 | 53.2 ± 17.2 | 67.7 ± 17.2 | 36.3 ± 18.2 |

| 3-8 | 38 | 64.1 $ 14.6 | 77.0 $ 15.8 | 80.9 $ 16.0 | 50.4 ‡ 17.6 |

| Mean difference | -15.1 | -21.9 | -12.2 | -14.1 | |

| 95% CI | -22.3 to -7.8 | -29.7 to -14.0 | -21.2 to -5.3 | -22.9 to -5.6 | |

| P value | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

Mortality

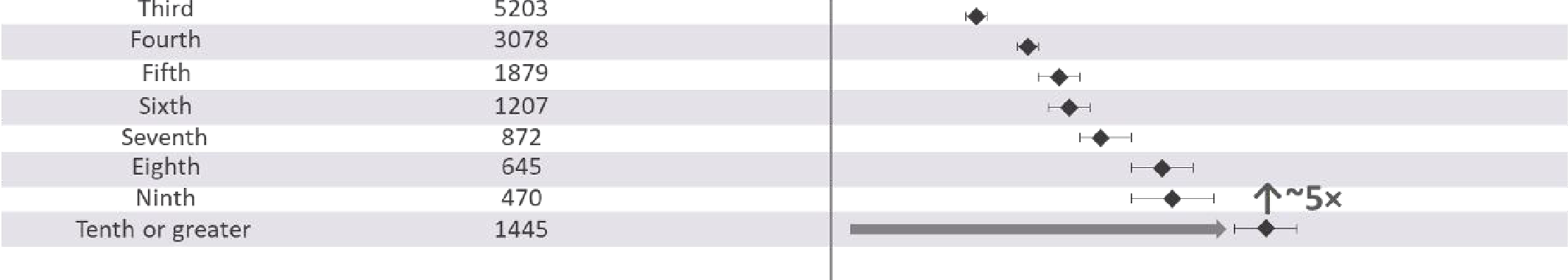

In a study of 73,106 COPD patients, the risk of death increased with each successive severe exacerbation experienced.

The rate of death after the second severe exacerbation was 1.9x higher than after the first, while after the 10th it was 5x higher than after the first.

HR for death increases with every successive severe exacerbation24

Lung function

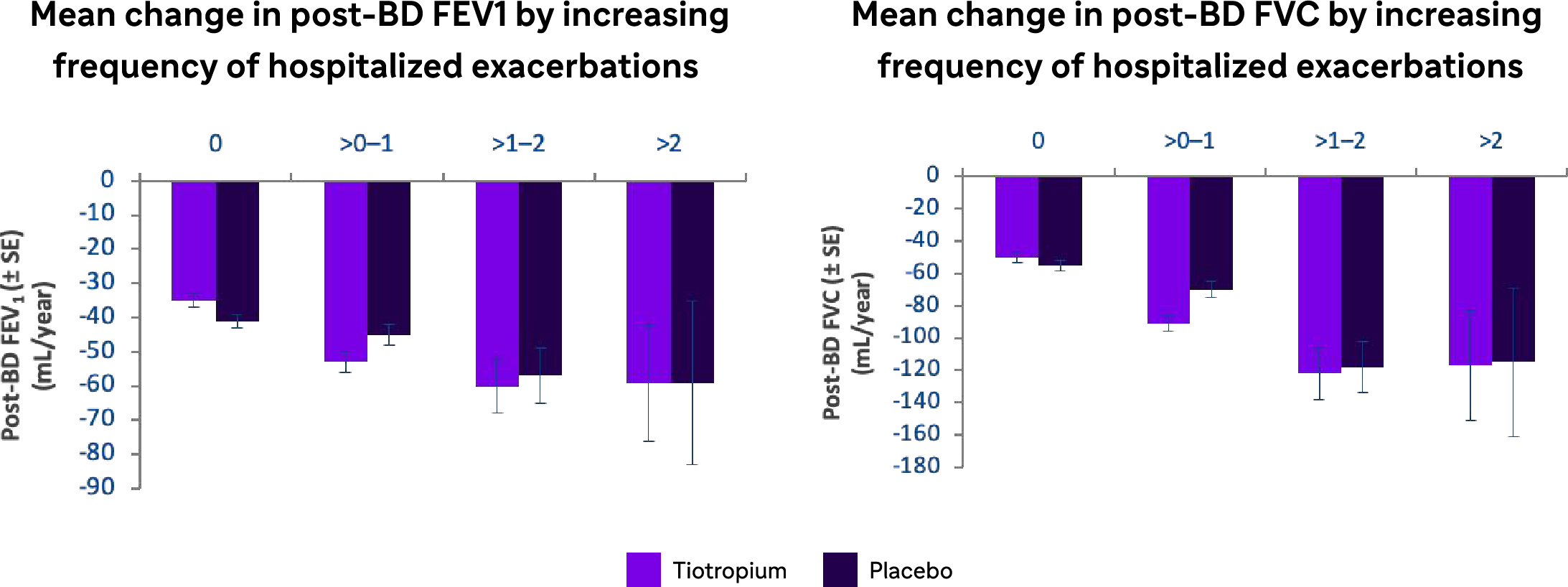

The UPLIFT study of 5,992 COPD patients observed that a higher frequency of severe hospitalized COPD exacerbations was associated with a marked decline in lung functions25.

Mean change in lung function parameters by increasing frequency of hospitalized exacerbations in the 4-year UPLIFT study25

@2x.png)

Exacerbations were defined as an increase in or the onset of more than one respiratory symptom (cough, sputum, sputum purulence, wheezing, or dyspnea) lasting 3 days or more and requiring treatment with an antibiotic or systemic corticosteroids.

BD, bronchodilator; FVC, forced vital capacity; SE, standard error.

Disease onset, course, and severity

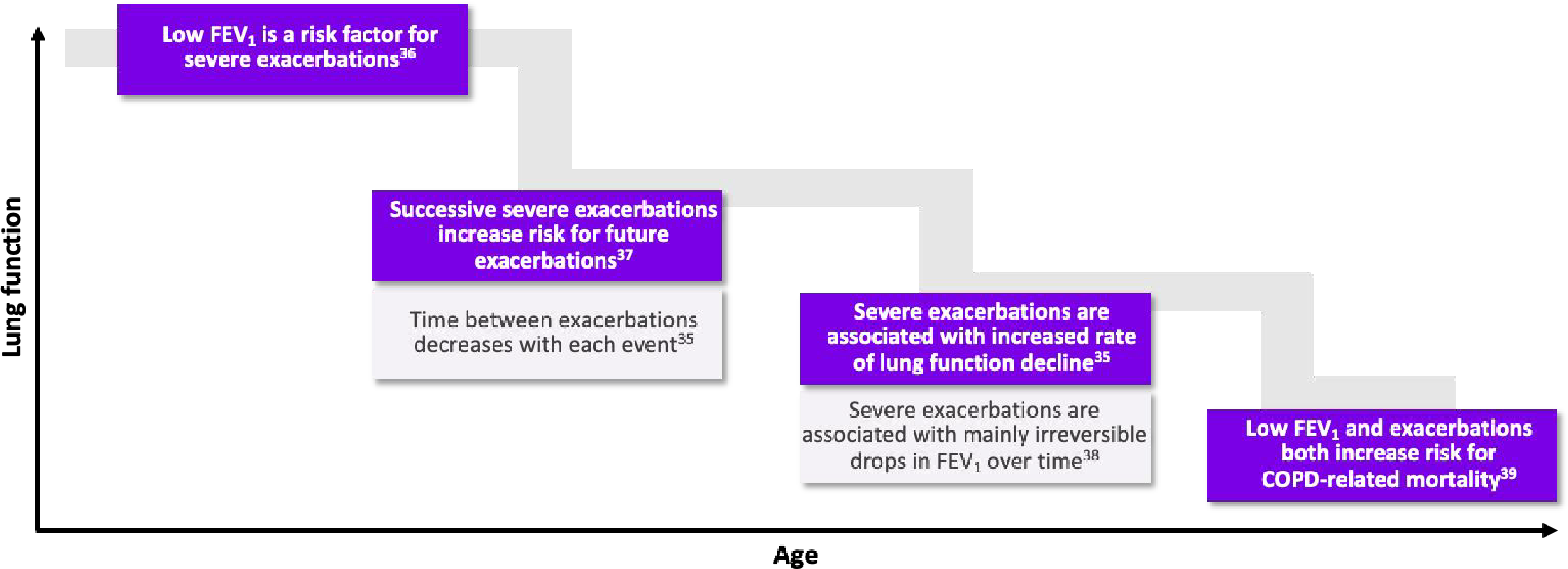

COPD can start early in life and take a long time to manifest clinically. As identifying early COPD can be difficult, patients are typically diagnosed with COPD aged > 40 years 31,32.

Morbidity due to COPD increases with age:

As lung function declines with age, patients experience more exacerbations, which increases the risk of future exacerbations and the rate of lung function decline31.

- Cook N, et al. Impact of cough and mucus on COPD patients: primary insights from an exploratory study with an Online Patient Community. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019; 14: 1365-1376.

- GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018; 392: 1859-1922.

- GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8(6): 585-596.

- Miravitlles M, et al. Observational study to characterise 24-hour COPD symptoms and their relationship with patient-reported outcomes: results from the ASSESS study. Respir Res. 2014; 15: 122.

- Jones PW, et al. Patient-centred assessment of COPD in primary care: experience from a cross-sectional study of health-related quality of life in Europe. Prim Care Respir J. 2012; 21: 329-336.

- Celli B, et al. Perception of symptoms and quality of life - comparison of patients' and physicians' views in COPD MIRROR study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017 Jul 27;12:2189-2196.

- Guarascio AJ, et al. The clinical and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the USA. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013; 5: 235-245.

- GOLD. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2023 Report. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/. Accessed June 2023.

- Wallace AE, et al. Health Care Resource Utilization and Exacerbation Rates in Patients with COPD Stratified by Disease Severity in a Commercially Insured Population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019; 25: 205-217.

- Poder TG, et al. Eosinophil counts in first COPD hospitalizations: a 1-year cost analysis in Quebec, Canada. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018; 13: 3065-3076.

- Chang J, et al. Prediction of COPD risk accounting for time-varying smoking exposures. PLOS one. 2021; 16(3): e0248535.

- CDC.gov. Health statistics. Available at: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/ SHS/2018_SHS_Table_A-12.pdf. Accessed June 2023.

- 13. Celli B, et al. Emphysema and extrapulmonary tissue loss in COPD: a multi-organ loss of tissue phenotype. Eur Respir J.2018;7:51:1702146.

- Woodruff PG, et al. Clinical Significance of Symptoms in Smokers with Preserved Pulmonary Function. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1811-1821

- Oelsner EC, et al. Lung function decline in former smokers and low-intensity current smokers: a secondary data analysis of the NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:34-44.

- Westerik JA, et al. Associations between chronic comorbidity and exacerbation risk in primary care patients with COPD. Respir Res. 2017; 18: 31.

- Mannino DM, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008; 32: 962-969.

- Alshabanat A, et al. Asthma and COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS): A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0136065.

- Wurst KE, et al. Disease Burden of Patients with Asthma/COPD Overlap in a US Claims Database: Impact of ICD-9 Coding-based Definitions. Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017; 14: 200-209.

- Sullivan PW, et al. Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018; 141(1): 110-116.

- GOLD. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2023 Report. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/. Accessed February 2023.

- NHS. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - Symptoms. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/ chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd/symptoms/. Accessed June 2023.

- MD+CALC. mMRC (Modified Medical Research Council) Dyspnea Scale. Available at: https://www.mdcalc.com/ calc/4006/mmrc-modified-medical-research-council-dyspnea-scale. Accessed June 2023.

- Rajala K, et al. mMRC dyspnoea scale indicates impaired quality of life and increased pain in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res. 2017 Oct; 3(4): 00084-2017.

- Leidy N, et al. Interpreting Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms™ in COPD Diary Scores in Clinical Trials: Terminology, Methods, and Recommendations. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2022; 9(4): 576-590.

- Tabberer M, et al. Measuring respiratory symptoms in moderate/severe asthma: evaluation of a respiratory symptom tool, the E-RS®: COPD in asthma populations. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021 Dec; 5: 104.

- Sciriha A, et al. Health status of COPD patients undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation: A comparative responsiveness of the CAT and SGRQ. Sage journals. 2017; 14(4):352-359

- American Thoriac society. St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). Available at: https:// www.thoracic.org/members/assemblies/assemblies/srn/questionaires/sgrq.php. Accessed June 2023.

- FDA. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Use of the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire as a PRO Assessment Tool. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary- Disease--Use-of-the-St.-George%E2%80%99s-Respiratory-Questionnaire-as-a-PRO-Assessment-Tool- Guidance-for-Industry.pdf. Accessed June 2023.

- American Thoriac society. COPD Assessment Test (CAT). Available at: https://www.thoracic.org/members/ assemblies/assemblies/srn/questionaires/copd.php. Accessed June 2023.

- Lareau S, et al. Exacerbation of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 198: 21-22.

- BMJ Best Practice. Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Available at: https:// bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/3000086/criteria. Accessed June 2023.

- Seemungal TA, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Critical Care Med. 1998; 157(5): 1418-1422.

- Suissa S, et al. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012; 67: 957-963.

- Halpin DMG, et al. Exacerbation frequency and course of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012; 7: 653-661.

- Garcia-Aymerich J, et al. Lung function impairment, COPD hospitalisations and subsequent mortality. Thorax. 2011;66:585-590.

- Suissa S, et al. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67:957-963

- Donaldson GC, et al. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57:847-852

- Flattet Y, et al. Determining prognosis in acute exacerbation of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:467-475.