From shared pathways toward therapeutic innovation`, author: ``, tags: `Immunology`, publication_date: ``, interaction_type: "content" }

- Article

- Source: Campus Sanofi

Expanding the landscape of Type 2 inflammation

From shared pathways toward therapeutic innovation

The symposium was held on 1st June 2025, from 09:30 to 12:00, at Lotus Suite 5–7, 22nd Floor, Centara Grand at Central World, Bangkok, Thailand. Expert presentations and clinical discussions were moderated by Assoc. Prof. Nopadon Noppakun, M.D. Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, ensuring a focused and engaging program.

Itch in Chronic Inflammatory Skin Diseases: The Shared and Distinct Contributions of Type 2 Inflammation

Prof. Brian Kim, M.D. Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, USA

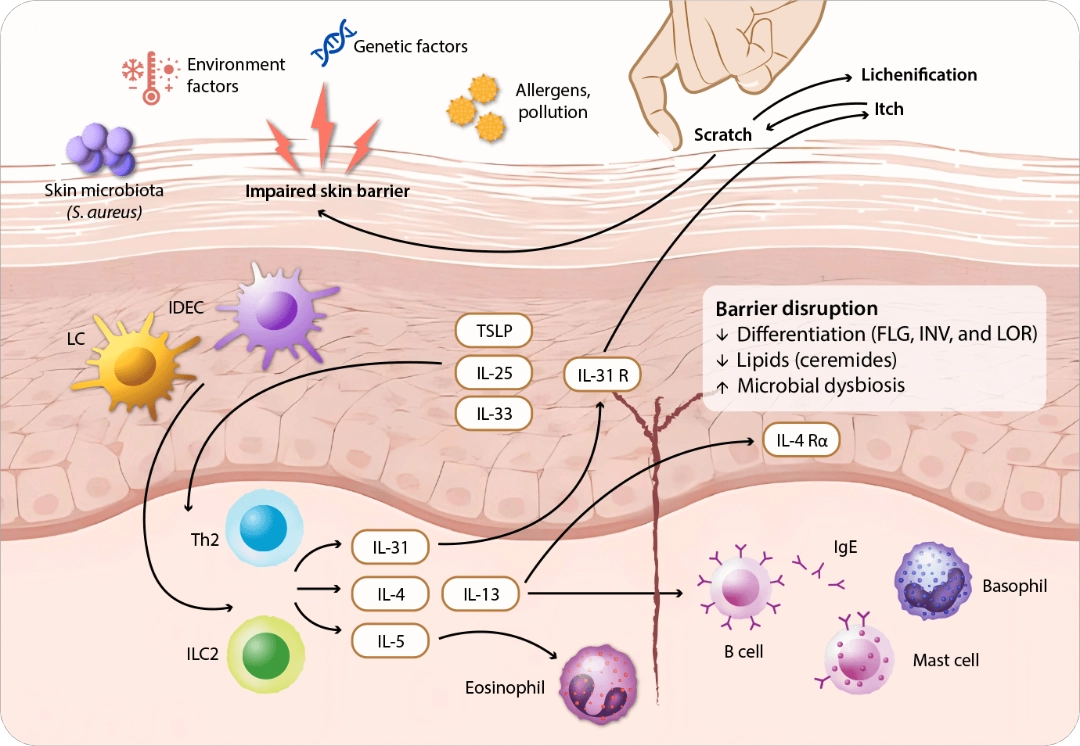

Itch is a diverse sensation that varies across skin disorders and significantly impairs patients’ quality of life.1-3 Type 2 inflammation, involving histaminergic and nonhistaminergic pathways, is a key driver of itch in chronic inflammatory skin diseases across atopic dermatitis (AD)4, prurigo nodularis (PN)5, chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU)6, and bullous pemphigoid (BP).7 With shared and distinct neuroimmune mechanisms, it drives itch severity and burden in each disease. The type 2 inflammation and sensory nerves interact dynamically in promoting the neuronal sensitization and stimulating chronic itch.8 Immune cells release type 2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31 that modulate sensory nerve activation and sensitization, while the sensory neurons secrete neuropeptides that influence cutaneous neurogenic inflammation (Figure 1).8,9

FLG, filaggrin; IDEC, inflammatory dendritic epidermal cell; IL, interleukin; ILC2, type 2 innate lymphoid cell; INV, involucrin; LC, Langerhans cell; LOR, loricrin; R, receptor; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; Th2, T helper 2; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Adapted from Huang IH, et al. Front Immunol. 13:1068260;2022.

Figure 1. Pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis.

Over half (61%) of patients with AD experienced severe or unbearable itch, along with frequent, long-lasting, itchy and painful skin on a daily basis.10 The complex interaction between skin barrier impairment, abnormal immune response and neural sensitization drives itch-scratch cycle.4 Scratching exacerbates skin inflammation which can intensify itching and often causes skin erosion, thus the treatment goal is free of itching.11 IL-4 plays a crucial role in immune sensitization by driving T helper 2 (Th2) differentiation, which produces IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31.12 These cytokines promote B-cell activation, immunoglobulin E (IgE) isotype switching and immune cells recruitment to the skin. Allergen-specific IgE binds to mast cells and basophils, triggering degranulation that increases itch flares and IL-4 production. In addition, IL-4 is associated with Janus kinase (JAK) 1 as a downstream signaling in the pathway driving immune-mediated conditions to promote B-cell activation and IgE production.13 Blocking IL-4 and its downstream effects explains the efficacy of IL-4 inhibitors in treating AD and related conditions.

The Latest Updates and Clinical Advancements in Prurigo Nodularis, Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria and Bullous Pemphigoid

The Path to Nodules: Type 2 Inflammation at the Core of Chronic Itch and Fibrosis in Prurigo Nodularis

Prof. Brian Kim, M.D. Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, USA

Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a chronic skin condition characterized by intense itch and various skin lesions including popular, nodular, plague, or umbilicated types.14 The itch affects both lesional and non-lesional skin, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life and psychological well-being.15,16 The type 2 inflammation drives the disease through immune dysregulation and neuronal dysfunction. IL-4 is a key upstream mediator driving Th2 differentiation and pruritogenic IL-31 production, leading to itch signaling.14,17 Consequently, IL-4 and IL-13 promote fibrosis by stimulating fibroblast proliferation and differentiation via TGF-β, increasing collagen and extracellular matrix deposition, potentially result in permanent scarring or dyspigmentation.7,18

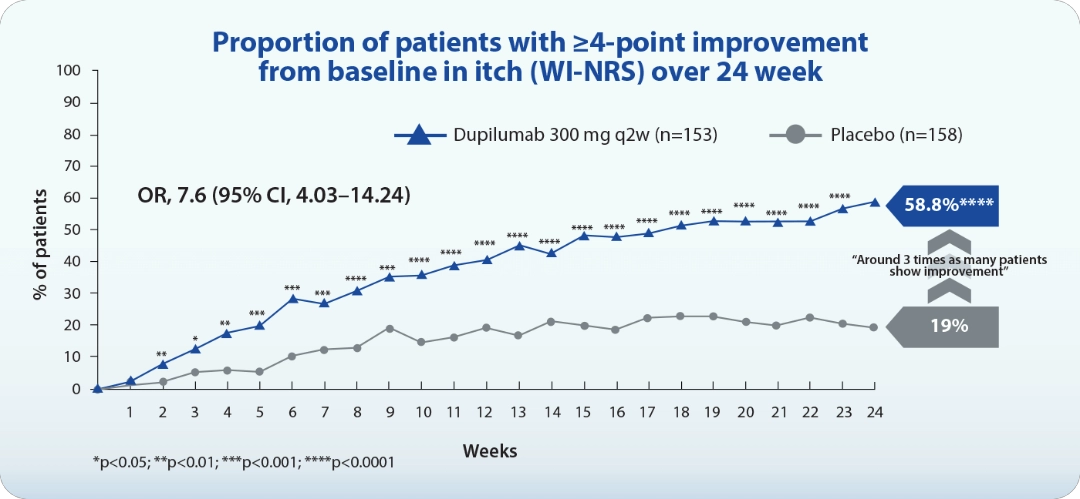

Dupilumab, a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-4Rα subunit of type I and type II receptors, which then blocks the signaling of IL-4 and IL-13 in type 2 inflammation. Phase 3 study showed dupilumab significantly improved itch from the first dose, with 58.8% achieving a ≥4-point reduction in Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) by week 24 in LIBERTY-PN PRIME/PRIME2 pooled (Figure 2).19 Dupilumab also significantly reduced skin lesion compared to placebo, with 46% of treated patients reaching an Investigator Global Assessment for PN-Stage (IGA PN-S) score of 0 or 1. The drug is well-tolerated and clinically meaningful for PN patients, interrupting the itch-scratch cycle and promoting nodule clearance through dual IL-4 and IL-13 inhibition.19

OR, odd ratio; q2w, every 2 weeks; WI-NRS, worst itch numerical rating scale. Adapted from Yosipovitch G, et al. JAAD Int. 2024;16(suppl):163-174.

Figure 2. Efficacy of dupilumab in the LIBERTY-PN PRIME and PRIME2 phase 3 trials.

Inside the Hive: Type 2 Inflammation Pathways in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

Prof. Kanokvalai Kulthanan, M.D. Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is characterized by the spontaneous appearance of wheals, angioedema, or both for over 6 weeks. The wheals usually present 30 minutes to 24 hours and resolves without residual marks.20 Type 2 inflammation plays role in CSU through mast cell and basophil activation and degranulation. This triggers release of histamine, proteases, and cytokines like IL-4 and IL-13, which amplify itch, promote IgE class switching, and recruit immune cells to the skin. These mediators cause vascular leakage, swelling, and neuronal sensitization, leading to characteristic symptoms.17,20

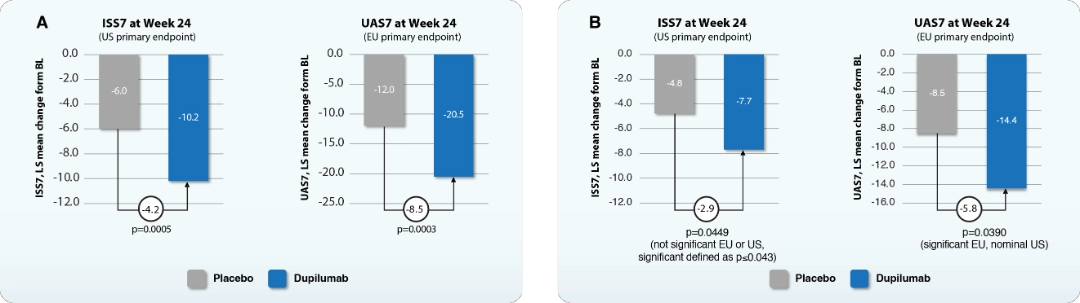

Dupilumab blocks IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, reducing vasodilation, vascular permeability, and sensory neuron sensitization, which decreases erythema, swelling, and itch in CSU.21 In LIBERTY-CSU CUPID study, dupilumab significantly improved urticaria activity by reducing itch and hive severity in omalizumab-naïve patients uncontrolled by H1 antihistamines over 24 weeks (CUPID Study A) (Figure 3A), regardless of IgE levels or atopic history.22 In omalizumab-intolerant/ incomplete responders (CUPID Study B), dupilumab showed significant improvement in weekly urticaria activity score (UAS7) but only a non-significant improvement of weekly itch severity score (ISS7) (p=0.0449) at week 24 (Figure 3B).22

BL, baseline; HSS7, weekly hives severity score; LS, least squares.

Adapted from Kanokvalai K. Presented at: Expanding the Landscape of Type 2 Inflammation from Shared Pathways toward Therapeutic Innovation: 1st June 2025; Bangkok, TH.

Figure 3. Efficacy of dupilumab in the LIBERTY-CSU CUPID study A (A) and study B (B) phase 3 trials.

Blister and Beyond: Autoimmune Meets Type 2 Inflammation in Bullous Pemphigoid

Lim Kar Seng, M.D. Mount Elizabeth Novena Specialist Centre, Singapore

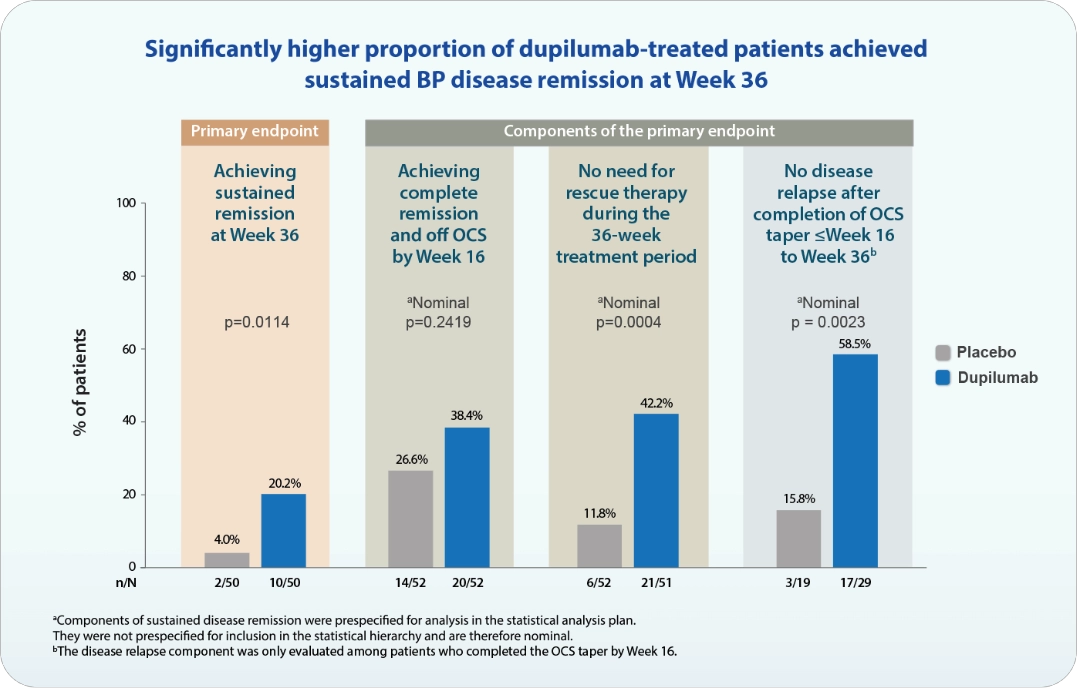

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a chronic, relapsing autoimmune skin disease and typically presents intense itch, inflammatory lesions, and blister.7 Diagnosis is often delayed due to its similarities with other conditions but it can be confirmed by skin biopsy or serum testing.7,23 BP involves loss immune tolerance and development of autoantibodies against BP180 and BP2307, triggering type 2 immune response. Cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 drive B-cell activation and IgE production. In addition, activated eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells release proteolytic enzymes that play a key role in forming subepidermal blisters in BP.4,7,24 In a phase 2/3 LIBERTY-BP ADEPT study, dupilumab, as IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, significantly sustained disease remission (p=0.0114), with patients requiring no rescue therapy and had no disease relapses (Figure 4). In addition, dupilumab significantly improved BP disease activity (p=0.0003) and itch (p=0.0006). The treatment also resulted in a lower cumulative corticosteroid dose over 36 weeks (p=0.0220) and increased the likelihood of discontinuing and remaining off oral corticosteroids (p=0.0002).25

N, number of patients with observed data for the endpoint; n, number of patients with observed responder status for the endpoint; OCS, oral corticosteroids.

Adapted from Seng LK. Presented at: Expanding the Landscape of Type 2 Inflammation from Shared Pathways toward Therapeutic Innovation: 1st June 2025; Bangkok, TH.

Figure 4. Efficacy of dupilumab in the LIBERTY-BP ADEPT phase 2/3 trials.

Beyond Skin Plenary: Can Early Intervention Alter the Progression of Type 2 Inflammatory Diseases?

Assist. Prof. Sira Nanthapisal, M.D. Thammasat University, Thailand

Atopic Dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin disease linked to skin barrier dysfunction, microbial dysbiosis, and filaggrin gene mutations.26 It often marks the beginning of the atopic march, increasing the risk of food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.27 AD also contributes to nonatopic comorbidities and long-term physical and mental health impacts.28-30 Early disease control is essential for disease modification. Downstream mediators of type 2 inflammation can be used as biomarkers in non-lesional skin or preclinical stages of AD4. Biomarkers such as CCL17 (TARC), serum IgE, and regulatory T cells help assess disease activity and treatment response.

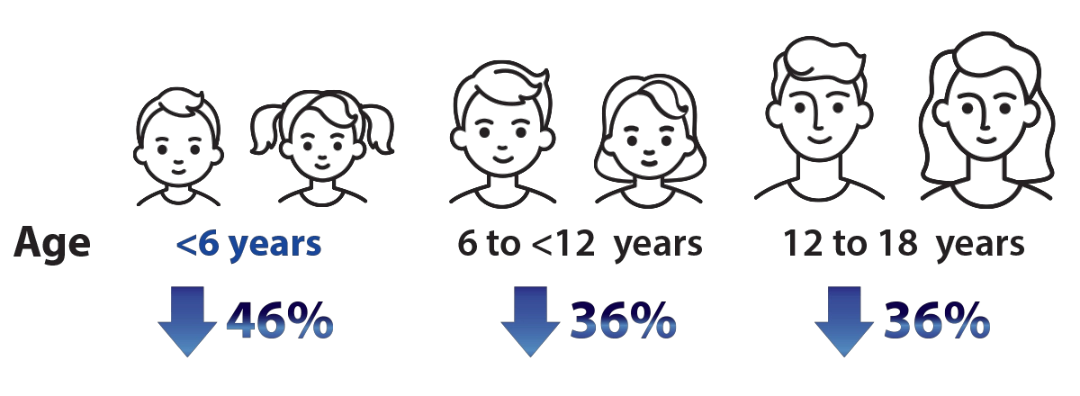

In LIBERTY AD PED-OLE study, dupilumab showed efficacy and safe treatment in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD over 16 weeks.31 Over half (53.7%) maintained clear or almost clear skin after 3 months off therapy.31 Dupilumab also lowered the risk of nonatopic comorbidities and progression of atopic march, including asthma or allergic rhinitis, compared with conventional systemic therapy (Figure 5).32 Food-specific IgE levels decreased notably within the first 16 weeks and continued to decline after one year.33

Case study – Severe infantile AD with multiple food allergy. The patient had a history of sever AD with hives, itchiness and AD flare triggered by cow milk and dairy products, as well as anaphylaxis to fish. After one year of dupilumab treatment, total IgE level decreased from 9,370 to 61.3 IU/mL, and the eczema area and severity index (EASI) score improved from 41 to 4.5. Following two years of dupilumab and three months off treatment, EASI further declined to 1.5 and the patient was able to consume any foods without reactions.

Abbreviations

AD, atopic dermatitis; BP, bullous pemphigoid; CCL17, C-C cytokine ligand 17; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; EASI, eczema area and severity index; Ig, immunoglobulin; IGA PN-S, investigator global assessment for PN stage; IL, interleukin; ISS7, itch severity score over 7 days; JAK, Janus kinase; PN, prurigo nodularis; R, receptor; TARC, thymus and activation-regulated chemokine; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; Th2, T helper 2; UAS7, urticaria activity score over 7 days; WI-NRS, worst itch numeric rating scale.

References

1. Akarsu S. Neuropathic Pruritus. In: Nduka JK, Akarsu S, eds. Rare Diseases - Recent Advances. IntechOpen; 2023. 2. Wimalasena NK, et al. Neuron. 2021;109(19):3075-3087.e2. 3. Wang F, Kim BS. Immunity. 2020;52(5):753-766. 4. Beck LA, et al. JID Innov. 2022;2(5):100131. 5. Zeidler C, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(2):173-179. 6. Radonjic-Hoesli S, et al. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):88-101. 7. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):320-332. 8. Kabata H, Artis D. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(4):1475-1482. 9. Sutaria N, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(1):17-34. 10. Simpson EL, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):491-498. 11. Augustin M, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):142-152. 12. Leyva-Castillo JM, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;154(6):1462-1471.e3. 13. Huang I-H, et al. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1068260. 14. Elmariah S, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):747-760. 15. Rodriguez D, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(11):1205-1212. 16. Misery L, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(7):e908-e909. 17. Gandhi NA, et al. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35-50. 18. Shao Y, et al. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1301817. 19. Yosipovitch G, et al. Nature Medicine. 2023;29(5):1180-1190. 20. Kolkhir P, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):61. 21. Le Floc’h A, et al. Allergy. 2020;75(5):1188-1204. 22. Maurer M, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;154(1):184-194. 23. van Beek N, et al. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1363032. 24. Giusti D, et al. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4833. 25. Murrell DF, et al. Adv Ther. 2024;41(7):2991-3002. 26. Irvine AD, et al. NEJM. 2011;365(14):1315-1327. 27. Choi UE, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;92(4):732-740. 28. Thyssen JP, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151(5):1155-1162. 29. Fasseeh AN, et al. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(12):2653-2668. 30. Kimball AB, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(9):989-1004. 31. Cork MJ, et al. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(11):2697-2719. 32. Lin TL, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91(3):466-473. 33. Yamamoto-Hanada K, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152(1):126-135.

Get a copy of this article for offline reading:

.jpg/jcr:content/image%20(17).jpg)