What is Bullous Pemphigoid

The heterogeneous presentation of bullous pemphigoid may shed light on why patients are underdiagnosed. Read the article to learn more

Bullous pemphigoid: A chronic disease with high clinical burden, mortality rates, and unmet needs1–6

Defining bullous pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is a chronic relapsing autoimmune skin disease, predominantly in those ≥60 years of age, characterized by intense itch, inflammatory lesions, and blister formation1, 6–11

Bullous pemphigoid at a glance…

Diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid can be delayed: The heterogeneous clinical presentation of bullous pemphigoid, in addition to the complexity of diagnostic tests, can lead to underdiagnosis7,12–15 |

Bullous pemphigoid can persist for months to years: Bullous pemphigoid has a mean duration of 105 months and a high relapse rate,1,6,16 with up to 53% of patients relapsing within 6 months of disease remission1 |

Intense itch is almost invariably present in patients with bullous pemphigoid: 85% of patients with bullous pemphigoid suffer daily from itch11 |

Bullous pemphigoid erosions or blisters are often associated with pain: 53% of patients with bullous pemphigoid report pain and of these, 26% report moderate-to-severe pain17 |

Type 2 inflammation is a critical driver of bullous pemphigoid pathogenesis: The pathophysiology of bullous pemphigoid involves autoimmunity to proteins BP180 and BP230 (components of adhesion complexes in the epidermis) and type 2 inflammation18–21 |

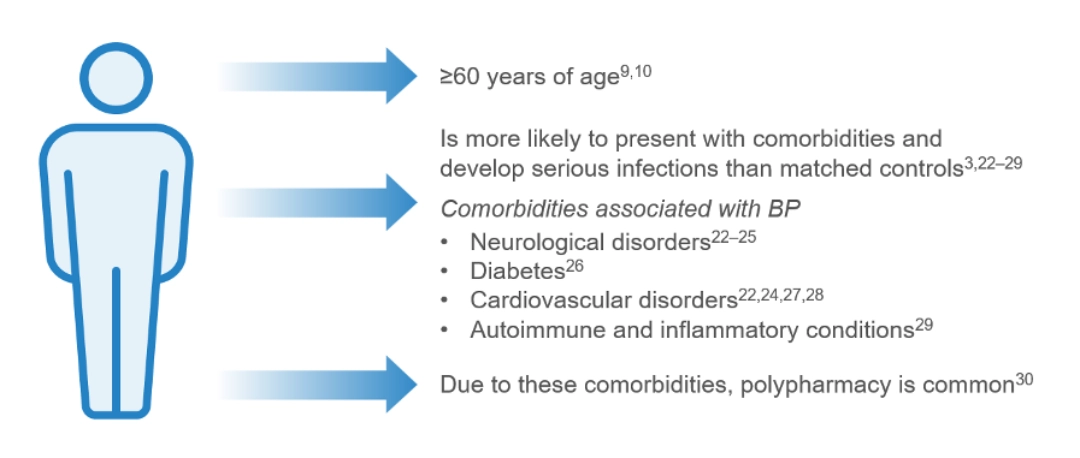

A typical patient with bullous pemphigoid:

The incidence of bullous pemphigoid varies globally,15, 31–37 with the reported worldwide incidence being 0.21–7.63 patients per 100,00038

The incidence of bullous pemphigoid has been rising over the past two decades, in part due to better recognition of clinical presentations of the disease, increased life expectancy of the general population and the increased use of certain drug triggers, such as:15,31,32,39–41

- Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (gliptins)

- Programmed death (PD)-1/programmed death-ligand (PDL)-1 inhibitors (and other immune checkpoint inhibitors)

- Loop diuretics

- Penicillin

What are the clinical presentations of bullous pemphigoid?

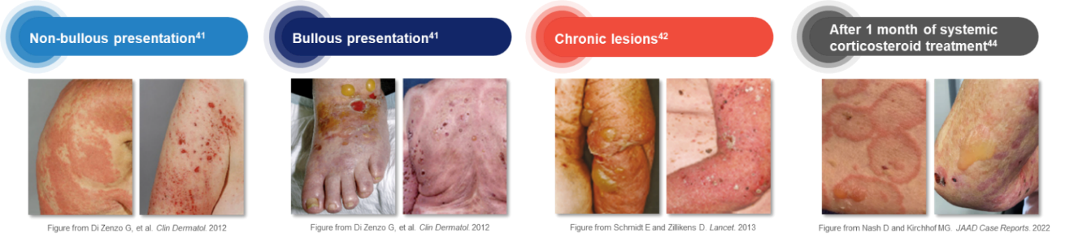

Bullous pemphigoid is characterized by intense itch and painful polymorphous lesions7,8,11,17,42–44

Bullous pemphigoid can present with or without bullous lesions7,15, 42–45

- Bullous presentation (~80%): Can consist of localized or generalized skin blisters arising from erythematous inflamed or normal-appearing skin7,8,42–44

- Non-bullous presentation (~20%): Can consist of urticarial, papular, eczematous lesions, and excoriations may be observed in the early phase of the disease or as the only manifestation of disease in certain patients7,8,15, 42–44

The non-bullous presentation of bullous pemphigoid can be confused with other dermatological conditions, such as atopic dermatitis or urticaria, adding to the burden of underdiagnosis; therefore, accurate identification is important7,13,46

How is bullous pemphigoid diagnosed?

Clinical assessment and obtaining patient history, in addition to techniques such as histopathology, immunofluorescence and/or ELISA are essential for bullous pemphigoid diagnosis; however, access to these resources vary widely by country and region12–14,47

Diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid12,13,42,47,48

In addition to the heterogenous clinical presentation of bullous pemphigoid, the complexity of diagnostic tests can contribute to underdiagnosis and diagnostic delays of up to 22 months7,12–16

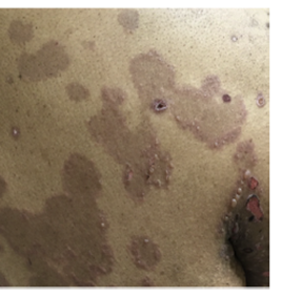

- Characteristics of bullous pemphigoid such as erythema may not be visible on skin of colora,46,49

- Dyspigmentation is more prominent on darker skin tones, which may be mistaken for other diseases46,49

|

|

|

aSkin of color includes African American, Filipino, Peruvian, Dominican, Indian, and Cambodian patients.46

|

The challenges of managing bullous pemphigoid

|

Morbidity and mortality in bullous pemphigoid

|

What are the contributing factors in bullous pemphigoid?

|

Current treatment approaches and unmet needs in bullous pemphigoid

|

- Wang Y, et al. Ann Med. 2018;50(3):234–9.

- Kridin K, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(1):72–7.

- Chang T-H, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:5329.

- Rice JB, et al. Clin Ther. 2017;39(11):2216–29.

- Kirtschig G, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(10):Cd002292.

- Aşkın Ö, et al. J Turk Acad Dermatol. 2020;14(2):53–6.

- della Torre R, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(5):1111–7.

- Schmidt E, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(1):133–6.

- Wertenteil S, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(3):655–9.

- Jung M, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2 Pt 1):266–8.

- Briand C, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(18):adv00320.

- Borradori L, et al. JEADV. 2022;36(10):1689–704.

- Amber KT, et al. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):26–51.

- Kridin K and Ahmed AR. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2466.

- Joly P, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(8):1998–2004.

- Lamberts A, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(2):224–5.

- Dan J, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(1):159–60.

- Messingham KA, et al. Immunol Res. 2014;59(1–3):273–8.

- van Beek N, et al. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(3):267–77.

- de Graauw E, et al. Allergy. 2017;72(7):1105–13;

- Cole C, et al. Front Immunol. 2022;13:912876.

- Bastuji-Garin S, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(3):637–43.

- Langan SM, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(3):631–6.

- Lai YC, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(12):2007–15

- Jeon HW, et al. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30(1):13–19.

- Zhang B, et al. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2022;13:20406223221130707.

- Cugno M, et al. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(1):193–9.

- Chen T-L, et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(17):e029740.

- Huttelmaier J, et al. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1196999.

- Försti A-K, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(6):758–61.

- Kridin K and Ludwig RJ. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:220.

- Persson MSM, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(1):68–77.

- Langan SM, et al. BMJ. 2008;337(7662):a180.

- Gudi VS, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(2):424–7.

- Marazza G, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(4):861–8.

- Bertram F, et al. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7(5):434–40.

- Brick KE, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):92–9.

- Rosi-Schumacher M, et al. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1159351.

- Tasanen K, et al. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1238.

- Verheyden MJ, et al. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(15):adv00224.

- Geisler AN, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255–268.

- Di Zenzo G, et al. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(1):3–16.

- Schmidt E and Zillikens D. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):320–2.

- Bernard P, et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(4):513–28.

- Nash D and Kirchhof MG. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;32:81–3.

- Tamazian S and Simpson CL. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(11):1173–8.

- Witte M, et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:296.

- Chatterjee T, et al. Cureus. 2022;14:e21770.

- Shah P, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185(2):430–2.