Smoldering Disease Burden

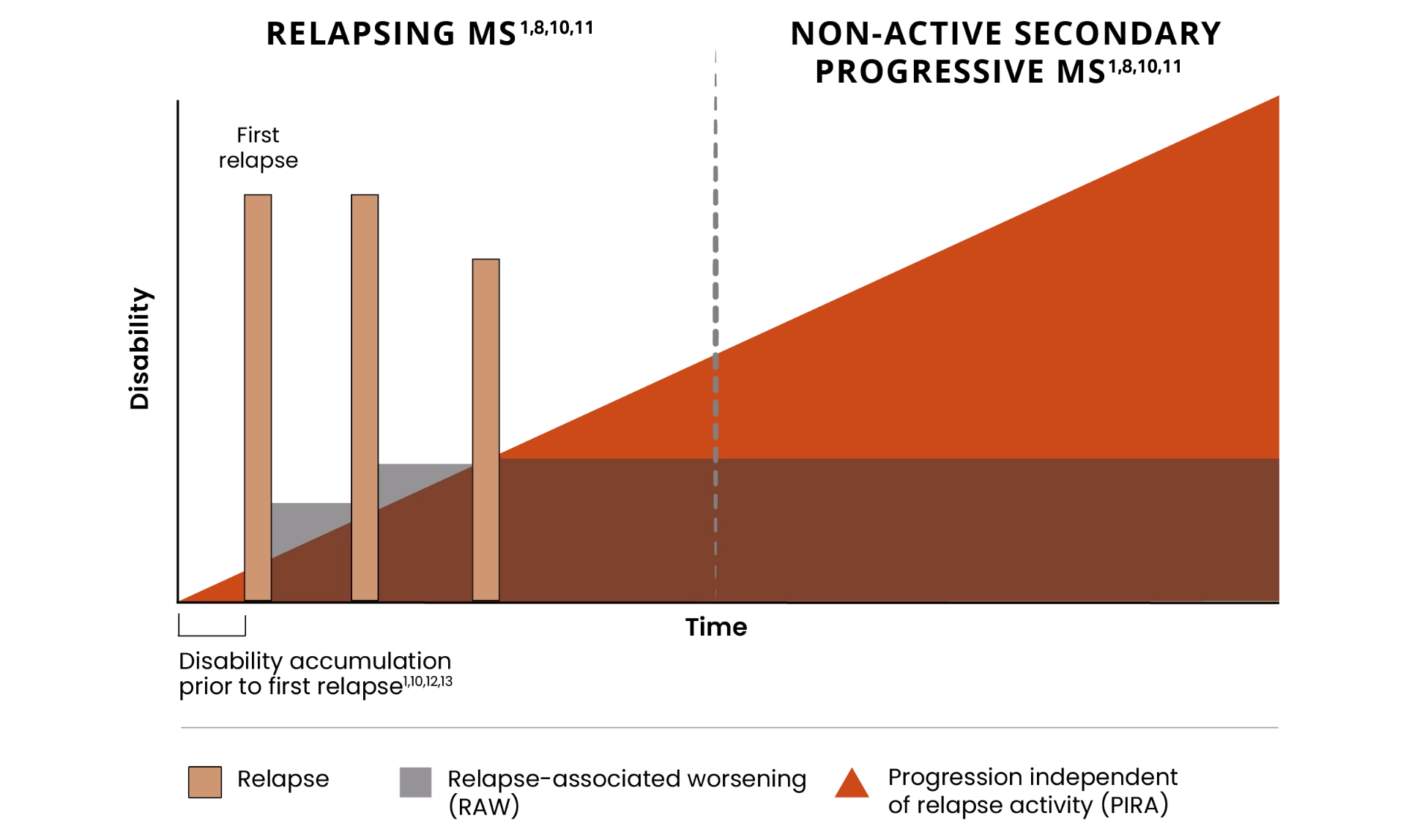

Despite effective control of relapses and acute lesions, many people with MS continue to accumulate disability.1,2

PIRA is responsible for up to 80% to 90% of disability accumulation in treated RRMS patients4,5*

*As documented by an observational study and pooled data from 2 randomized clinical trials.6,7

Many patients still progress from RRMS to SPMS and accumulate significant disability despite current treatments that effectively address relapses and acute lesions.1,2,15

Approximately

30% to 40%

of treated patients will transition to SPMS within 12 years of RRMS diagnosis6

*As documented by an observational study and pooled data from 2 randomized clinical trials.4,5

PIRA can occur early in the course of MS3,7

65% of RRMS patients reported

experiencing PIRA8,9

![]()

PIRA can be seen in treated RRMS patients as early as 3 years after diagnosis3,7

![]()

*As seen in real-world data (patient-reported outcomes). PIRA was defined as continuous worsening of symptoms independent of relapses in the previous 12 months.9

The damage from smoldering neuroinflammation can accumulate slowly and manifest as gradual physical and/or cognitive changes over years prior to transitioning to nrSPMS2,12

Physical decline may present as13,14:

![]()

- Reduced mobility and having to stop or decrease playing sports, such as tennis, running, etc

- Debilitating fatigue

- Worsening bladder and bowel control, vision, speech, and spasticity/dexterity

- Sexual dysfunction

- Pain

Cognitive decline may present as13:

![]()

- Trouble concentrating

- Experiencing difficulty multitasking

- Being less productive at work, or having more difficulty completing activities at work

- Brain "fog" and memory impairment

- Changes in mood/personality and reduced social activities

Symptoms could be gradually building before revealing themselves as clinically detectable disability accumulation, so it is important to continue monitoring patients for

changes over time.2

For more information about Acute and Smoldering Inflammation, click on this link:

MS=multiple sclerosis; PIRA=progression independent of relapse activity; RRMS=relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS=secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; nSPMS=non-relapsing secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; RAW=relapse-associated worsening.

- Giovannoni G, Popescu V, Wuerfel J, et al. Smouldering multiple sclerosis: the 'real MS'. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022;15:17562864211066751. doi:10.1177/17562864211066751:

- Katz Sand I, Krieger S, Farrell C, Miller AE. Diagnostic uncertainty during the transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20(12):1654-1657.

- Lakin L, Davis BE, Binns CC, Currie KM, Rensel MR. Comprehensive approach to management of multiple sclerosis: addressing invisible symptoms—a narrative review. Neurol Ther. 2021;10(1):75-98.

- Plotas P, Nanousi V, Kantanis A, et al. Speech deficits in multiple sclerosis: a narrative review of the existing literature. Eur J Med Res. 2023;28(1):252. doi: 10.1186/s40001-023-01230-3

- Müller J, Cagol A, Lorscheider J, et al. Harmonizing definitions for progression independent of relapse activity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(11):1232-1245.

- Koch MW, Mostert JP, Wolinsky JS, et al. Comparison of the EDSS, Timed 25-Foot Walk, and the 9-Hole Peg Test as clinical trial outcomes in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2021;97(16):e 1560-e 1570. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012690

- Brochet B, Deloire MSA, Bonnet M, et al. Should SDMT substitute, for PASAT in MSFC? A 5-year longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2008:14(9):1242-1249.

- Gil-González I, Martín-Rodríguez A, Conrad R, Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ. Quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e041249. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041249

- Feinstein A, Amato MP, Brichetto G, et al. Study protocol: improving cognition in people with progressive multiple sclerosis: a multi-arm, randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of cognitive rehabilitation and aerobic exercise (COGEx). BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):204. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-01772-7

- Kheirouri S, Alizadeh M. Dietary inflammatory potential and the risk of neurodegenerative disease in adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2019;41(1):109-120.

- Filippi M, Amato MP. Avolio C, et al. Towards a biological view of multiple sclerosis from early subtle to clinical progression: an expert opinion. J Neurol. 2025;272:179. doi:10.1007/s00415-025-12917-4

- Portaccio E, Bellinvia A, Fonderico M, et al. Progression is independent of relapse activity in early multiple sclerosis: a real-life cohort study. Brain. 2022;145:2796-2805.

- Bayas A, Schuh K, Christ M. Self-assessment of people with relapsing-remitting and progressive multiple sclerosis towards burden of disease, progression, and treatment utilization-results of a large-scale cross-sectional online survey (MS Perspectives). Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;68:104166. doi: 10.1016/i.msard.2022.104166

- Frisch ES, Pretzsch R, Weber MS. A milestone in multiple sclerosis therapy: monoclonal antibodies against CD20—yet progress continues. Neurotherapeutics. 2021;18(3):1602-1622.