Enhancing quality and improving outcomes: patient-first approach in Fabry disease

ENHANCING PATIENT-CENTRIC CARE IN FABRY DISEASE

• Understanding Nonadherence:

Medication nonadherence is a common and complex issue, affecting 40-50% of patients with chronic conditions. It is important to emphasize that nonadherence is not just a patient problem but a systemic and public health problem.1

• Factors Affecting Adherence:

Key factors include motivation, health literacy, cost, time constraints, alternative belief systems, treatment of

asymptomatic disease, poor provider-patient relationship, inconvenience, depression, denial, cognitive impairment, substance use, treatment

complexity, side effects, and cultural issues.1

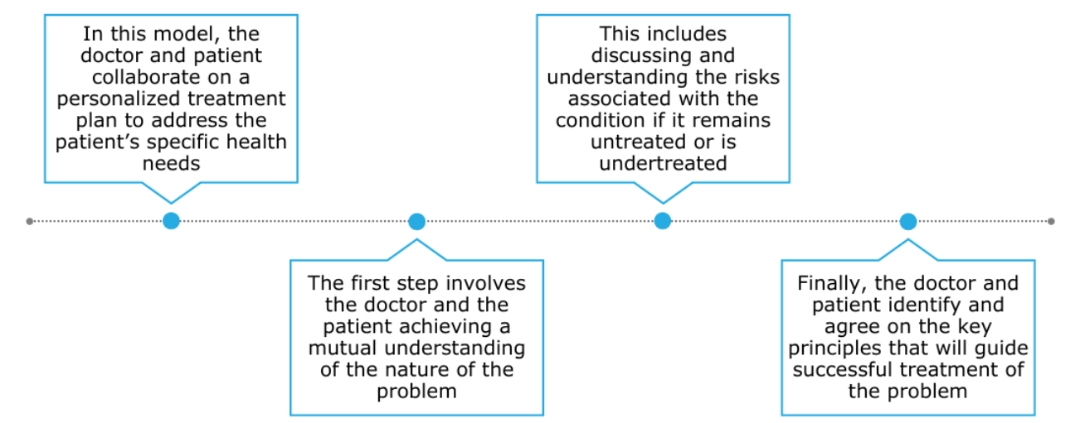

• Strategies for Improving Adherence:

A multi-faceted approach is needed, including better physician-patient communication, shared decision-

making, and team-based care. The importance of using open-ended, non- judgmental questions to assess adherence is emphasized.1,2,3

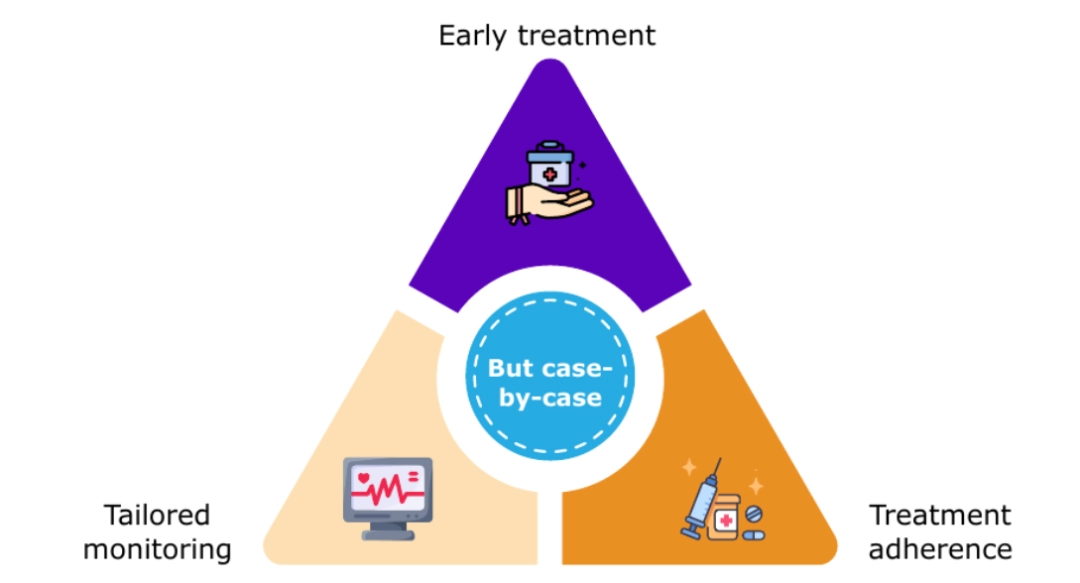

• Patient-Centric Approaches in Fabry Disease:

It is important to implement personalized care, considering factors such as disease phenotype,

sex, age, and X-chromosome inactivation patterns in females. Treatment should be tailored to each patient's unique circumstances.4-9

• Early Treatment in Children:

There is evidence supporting early initiation of ERT in children with classic Fabry disease, even before the onset of

symptoms. This approach aims to normalize biomarkers and potentially prevent disease progression.5,6

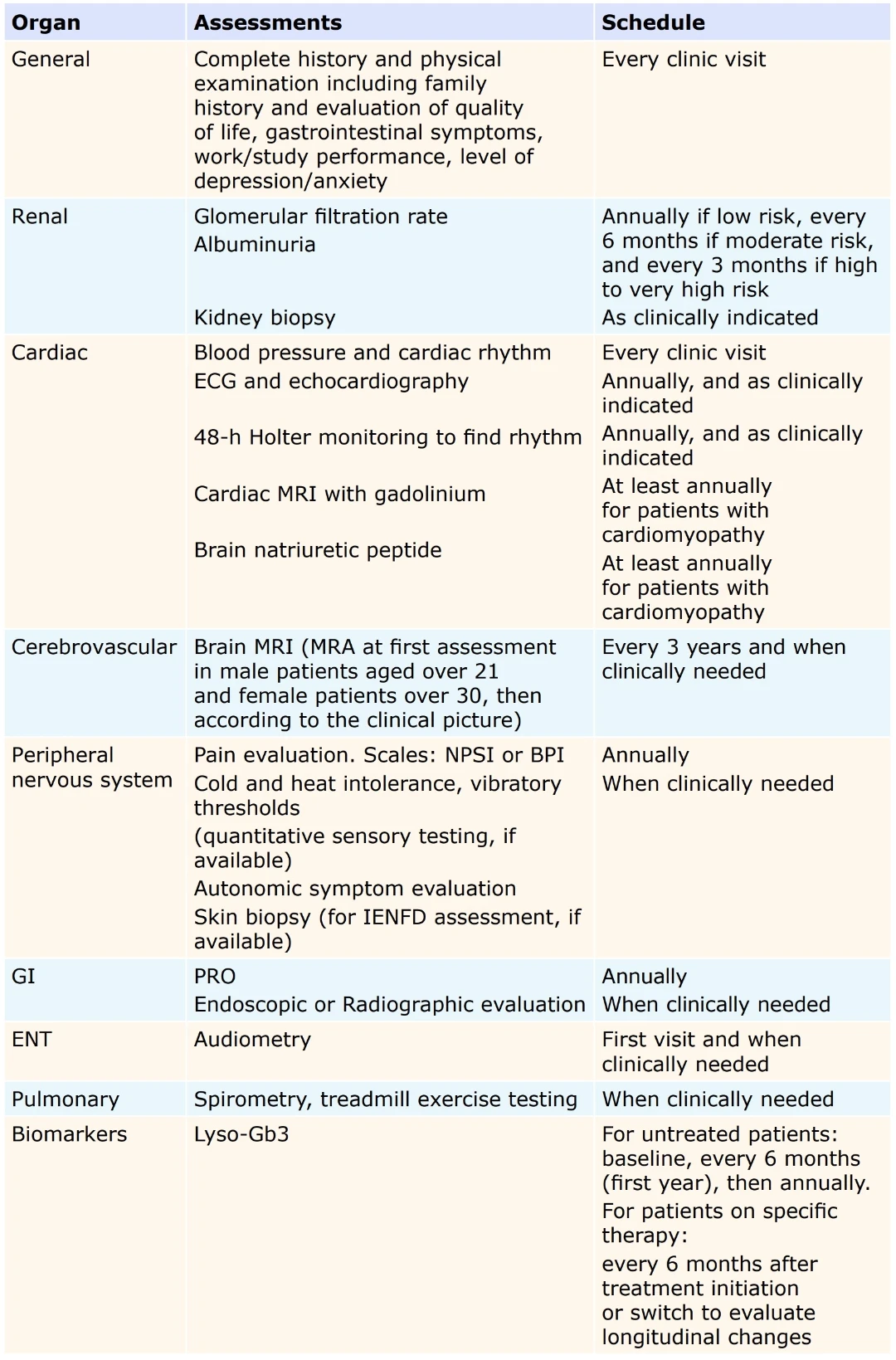

• Monitoring and Follow-Up:

Regular monitoring and follow-up for both treated and untreated patients is crucial. PROs can be used to complement

clinical assessments and tailor follow-up schedules based on age and phenotype.7,10-13

• Therapeutic Goals and Treatment Evaluation:

It is important to establish clear therapeutic goals and criteria for switching therapies. Biomarkers such

as lyso-Gb3 should be reduced as much as possible, particularly in classic

males with no residual enzyme activity.7,14-17

• Incorporating PROs:

Validated tools for assessing PROs may provide valuable insights into the patient’s QoL and symptom burden. PROs

should be tailored to age, phenotype, and specific symptoms to ensure a comprehensive assessment and effective management.7,10-13

Note, when you press "Watch the webinar!" you are leaving our website and entering an external site - The Rare Diseases University. To access the content, you will need to create an account.

MONITORING OF TREATED AND UNTREATED PATIENTS7,15

Therapeutic goals should be personalized.

ACHIEVING SUCCESS IN A PATIENT-CENTERED APPROACH

ADDRESSING NONADHERENCE IN FABRY DISEASE1,2,18,19

• Diagnosis and prescription are the first of many steps needed to successfully

control chronic conditions.

• Patients need to be educated and engaged, in a manner that is respectful,

interactive, and tailored to their health literacy level, socioeconomic status, and cultural background.

Physician–Patient Communication2

Shared Decision-Making2

The best understanding of the reasons for nonadherence will come from the patients with Fabry disease themselves—either from discussions

with individual patients or with focus groups.

Patients should be provided the opportunity to share their lived

experiences with Fabry disease.

Additional Approaches

• Educating patients as well as primary care physicians

• Setting realistic expectations

• Developing readily available and easy-to-read patient educational materials

• Tracking adherence to Fabry disease-specific therapy and reaching out to

nonadherent patients

• Asking nonadherent patients about why they are being irregular with therapy and addressing these issues

BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; ECG, electrocardiogram; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; ERT, enzyme

replacement therapy; GI, gastrointestinal; IENFD, intraepidermal nerve fiber density; lyso-Gb3, globotriaosylsphingosine; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NPSI, Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory; PRO, patient-reported outcome; QoL, quality of life.

References

1. Kleinsinger F. Perm J. 2018;22:18-033.

2. Kleinsinger F. Perm J. 2010;14(1):54-60.

3. Nieuwlaat R, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(11):CD000011.

4. Hopkin RJ, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;117(2):104-13.

5. Germain DP, et al. Clin Genet. 2019;96(2):107-117.

6. Kritzer A, et al. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2019;21:100530.

7. Ortiz A, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;123(4):416-427.

8. Wagenhäuser L, et al. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2022;10(9):e2029.

9. Rodríguez Doyágüez P, et al. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2023;43 Suppl 2:91-95.

10. Hamed A, et al. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2021;29:100824.

11. Jovanovic A, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):296.

12. Ramaswami U, et al. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012:10:116.

13. Shields A, et al. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(10):2983-2994.

14. Wanner C, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;124(3):189-203.

15. Germain DP, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2022;137(1-2):49-61.

16. Lenders M, et al. J Med Genet. 2019;56(8):548-556.

17. Bichet DG, et al. Genet Med. 2021;23(1):192-201.

18. Gast A, et al. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):112.

19. Delamater A, et al. Clin Diabetes. 2006;24(2):71-77.