Act early, think holistically for your patients with Type 2 diabetes at very high cardiovascular risk

People with type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease face a high risk of cardiovascular events, yet many remain undertreated.1 The EASD/ADA 2022 and ESC 2023 guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes urge early insulin initiation and intensive lipid lowering through a holistic approach. Managing both glycemia and lipids together is key to preventing CV events in people with type 2 diabetes.2,3

|

|

The latest data from the International Diabetes Federation highlights that diabetes is one of the fastest-growing global health threats of the 21st century, with T2D accounting for more than 90% of cases.4

|

2 out of 3 deaths

in people with T2D is due to CVD*1

Most people with T2D do not achieve their treatment targets, significantly increasing the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).5-10

|

|

This is despite mounting evidence linking insufficient control of key modifiable risk factors with adverse outcomes, for example, people with T2D are up to a 4x higher risk of developing CVD during their lifetime, and the presence of ASCVD significantly increases the CV risk.3 This gap in target achievement is reflected across multiple modifiable risk factors in people with T2D: |

|

|

have their blood pressure uncontrolled†5 |

|

|

do not achieve their HbA1c treatment target†5 |

|

|

do not achieve their LDL-C treatment targetऴ6-8 |

|

|

are overweight or obese9 |

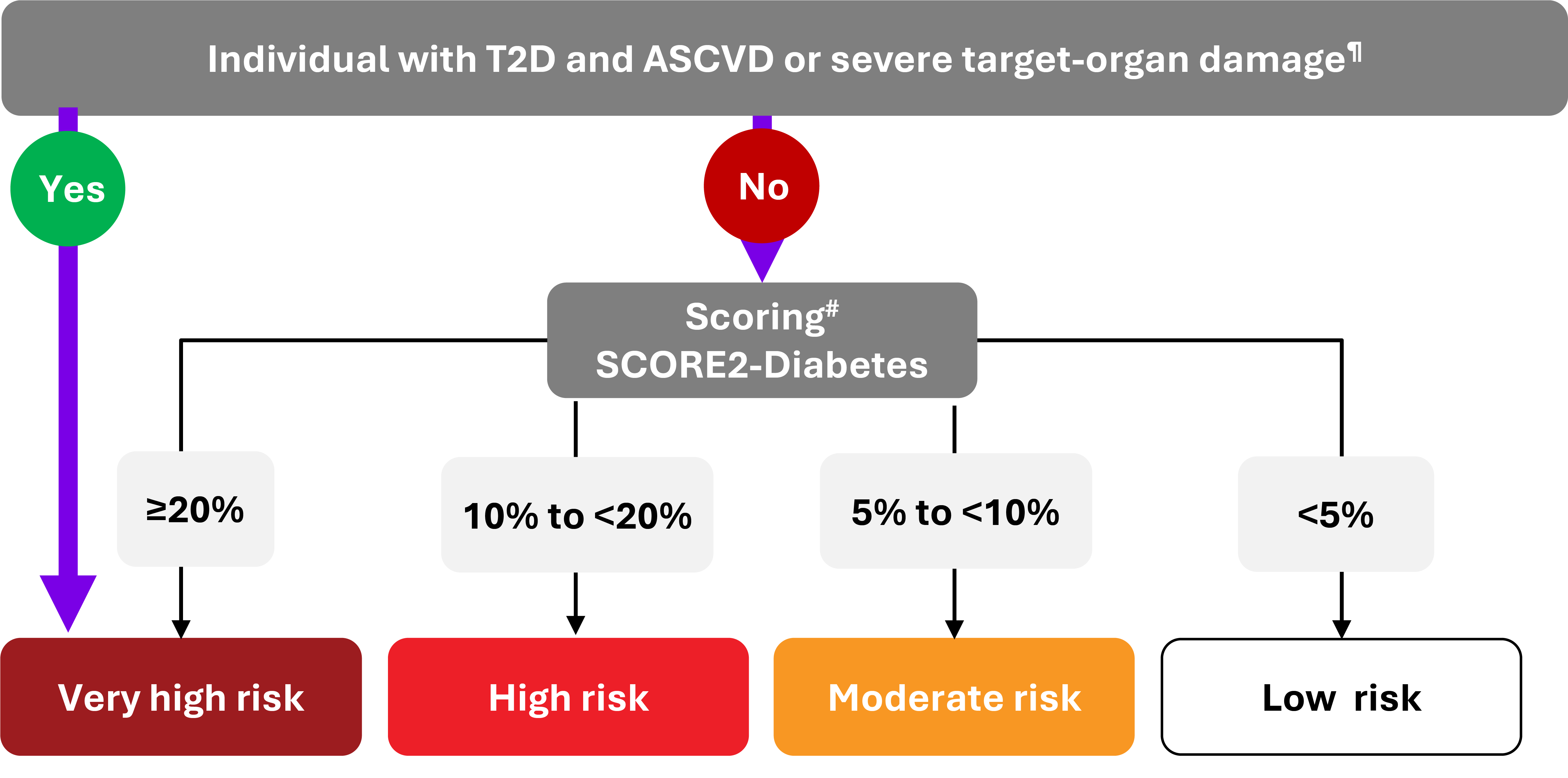

This low rate of target achievement has critical implications for CV risk assessment and management. The 2023 ESC Guidelines emphasize that individuals with T2D who already have ASCVD or severe target-organ damage are automatically classified as very high risk. For others, CVD risk is stratified using the SCORE2-Diabetes algorithm based on estimated 10-year CV risk.3

However, given that the majority of people with T2D do not achieve recommended targets for blood pressure, HbA1c, LDL-C, or weight, a large proportion are likely to fall into high- or very high-risk categories.3

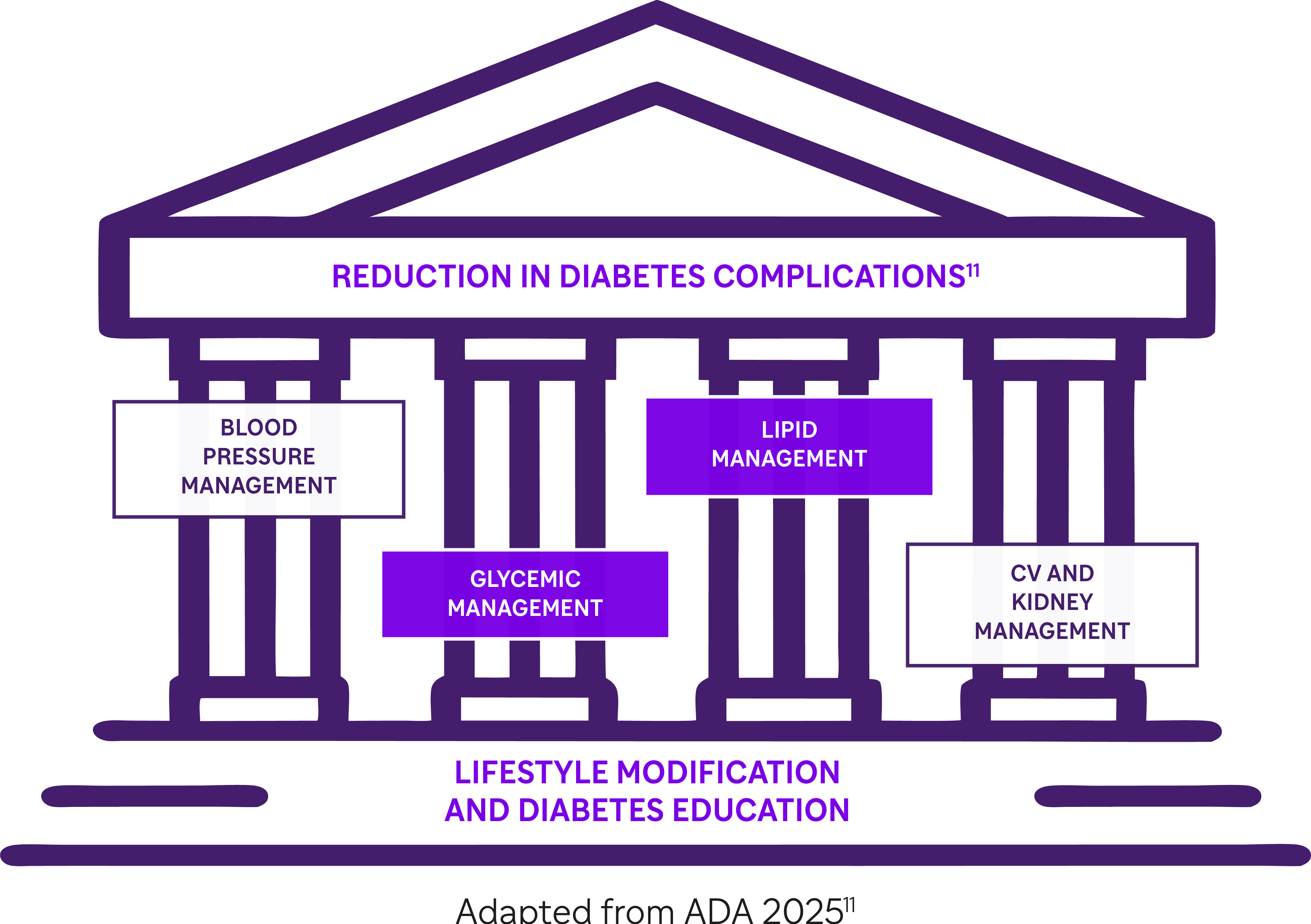

This highlights the urgent need for intensified and multifactorial intervention to close these gaps, in line with international treatment goals.2,3,11

2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of CVD in people with T2D3

|

|

In this context, the EASD/ADA 2022 and 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of T2D emphasize the need for a holistic multifactorial approach including appropriate glycemic and lipidic control to reduce the risk of CV complications.2,3 |

Yet, therapeutic inertia still persists:

Despite clear guidelines advocating timely intensification of treatment, people with T2D often experience prolonged periods of insufficient glycemic control. A large retrospective UK study of over 80,000 patients found that, among those with HbA1c above-target thresholds, time to insulin initiation exceeded 7 years, even in those already receiving two or more oral antidiabetic drugs.**12

Similarly, lipid-lowering treatment in high- and very high-risk patients remains suboptimal. Although guidelines increasingly recommend early and intensive LDL-C reduction, real-world evidence shows that many patients fail to reach lipid targets due to underuse of combination therapy. A recent global analysis of dyslipidemia care reported limited uptake of ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors, even in patients with established ASCVD.††13

Act timely to help your patients with T2D reach HbA1C and LDL-C goals

|

|

What do the 2022 EASD/ADA Guidelines recommend for glycemic control in people with inadequately controlled T2D?The latest EASD/ADA consensus guidelines recommend: “When glycemic measurements do not reach targets and insulin is the best choice for the individual, its introduction should not be delayed”.2 |

EASD/ADA 2022

“Longer-acting basal insulin analogs have a lower risk of hypoglycemia than earlier generations of basal insulin”2

EASD/ADA 2022 consensus guidelines for the management of T2D

|

|

What do the 2023 ESC Guidelines recommend for lipidic control in people with T2D at very high CV risk?People with T2D and clinically established ASCVD are defined as very high risk, and this population should aim for an LDL-C target of <55 mg/dL, and a reduction of at least 50%.‡‡3 The 2023 ESC Guidelines emphasize an intensive approach to LDL-C in these very high CV-risk populations and recommend:3 |

ACT TIMELY TO HELP YOUR PATIENTS WITH T2D

REACH HbA1c AND LDL-C GOALS

* About two-thirds of deaths in people with T2D are due to cardiovascular disease: of these, approximately 40% are from ischemic heart disease, 15% from other forms of heart disease, principally congestive heart failure, and about 10% from stroke.1

† Meta-analysis of 24 observational studies (n=369,251) from 20 countries to evaluate global attainment of ADA, EASD, and NICE treatment targets in adults with T2D. Data from 2006–2017 showed that only 42.8% achieved HbA1c goals, 29.0% reached blood pressure targets, and 49.2% met LDL-C thresholds, with significant variation by region and no improvement over time.5

‡ Multicenter Spanish study (n=380) evaluating LDL-C goal attainment in T2D patients across 7 endocrinology clinics. Based on 2016 and 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines, only 62.1% and 39.7% of patients, respectively, met LDL-C targets – despite 72.1% being classified as very high-risk. Treatment was adjusted in just 36.1% of those not at goal.6

§ Cross-sectional study in the Netherlands (n=428) showed that while 78% of high-risk T2D patients reached LDL-C ≤2.5 mmol/L, only 43% met the <1.8 mmol/L goal. Poor adherence to lifestyle guidelines was widespread, and high-intensity statin use remained uncommon among those not at goal.7

¥ Observational study in France (n=654) found 59% of patients with diabetes at very high cardiovascular risk failed to meet LDL-C targets (<1.8 mmol/L) despite statin therapy.8

¶ Severe target-organ damage defined as eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2 irrespective of albuminuria; or eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 and microalbuminuria (UACR 30– 300 mg/g; stage A2); or proteinuria (UACR >300 mg/g; stage A3), or presence of microvascular disease in at least three different sites [e.g. microalbuminuria (stage A2) plus retinopathy plus neuropathy].3

# The thresholds (10-year CVD risk) suggested are not definitive but rather designed to prompt joint decision-making conversations with patients about intensity of treatment, as well as additional interventions. SCORE2-Diabetes refers to patients aged ≥40 years.3

** Observed in a large retrospective cohort of over 81,000 UK patients, where the median time to insulin intensification was >7.1 years in those already on two or three oral antidiabetic drugs, and >6.0 years even at higher HbA1c thresholds. Mean HbA1c at insulin initiation exceeded 9% in most cases.12

†† Observed in a prospective, multinational, observational, non-interventional cohort study conducted across 14 European countries between 2020 and 2021. It enrolled 9,602 adults at high or very high cardiovascular risk to document real-world lipid-lowering therapy use and LDL-C goal attainment based on 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines. Statin monotherapy was used in 50.2% of all patients (54.5% and 48.4% of patients in the high- and very high-risk groups, respectively). The use of other LLT as monotherapies among all patients was low: 1.8% on ezetimibe, 1.7% on PCSK9 inhibitors, and 0.6% on other oral LLT. Combination LLT were used in 24.0% of all patients and more frequently used in the very high-risk group (26.4%), compared with the high-risk group (18.1%). Combination therapy includes: 16.0% of patients on statin plus ezetimibe, 4.5% on a PCSK9 inhibitor plus oral LLT, 3.5% receiving any other oral combination therapy. The pattern was similar for patients with and without ASCVD.13

‡‡ Patients with severe target-organ damage or 10-years CVD risk ≥20% using SCORE2-Diabetes are also classed as very high CV risk.3

ADA, American Diabetes Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; EASD, European Association for the Study of Diabetes; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LLT, lipid-lowering therapy; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; SCORE, systematic coronary risk estimation; SGLT2i, sodium/glucose transporter-2 inhibitor; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TIR, time-in-range; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

-

Wang CCL, et al. Circulation. 2016;133:2549–502.

-

Davies MJ, et al. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:2753–2786.

-

Marx N, et al. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(39):4043–4140.

-

International Diabetes Federation (IDF). IDF Diabetes Atlas 11th Edition. Available at: https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/# (Accessed August 2025).

-

Khunti K, et al. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:137–148.

-

Villar-Taibo R, et al. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed). 2023;70(1):29–38.

-

Gant CM, et al. Nutr Diabetes. 2018;8(1):24.

-

Breuker C, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2018;268:195–199.

-

Grant B, et al. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(4):e327–e231.

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (Accessed August 2025).

-

American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Supplement_1):S207–S238.

-

Khunti K, et al. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3411–3417.

-

Ray KK, et al. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;29:100624.